Origins of the Enneagram center construct

The origins of the Enneagram center construct can be found in the work of Evagrius, a Christian philosopher who lived outside of Alexandria in the 4th century.

Evagrius was part of a movement of disaffected Christians who left behind their traditional lives in order to live and work in solitude in the Egyptian desert during the fourth and fifth century. Collectively these Christians came to be known as the Desert Fathers and Mothers and their philosophy and practices formed the foundation of Christian monasticism1. Evagrius was one of this tradition’s most influential teachers. A major part of his work involved re-imagining two key concepts - the tripartite soul and the logisimoi (generic, disordered, irrational thoughts that were thought to upset and distract humans). These concepts had been passed down from earlier Egyptian and Greek philosophical traditions and incorporated into the newly evolving Christian theology.

Wiltse and Palmer (2011) point out in their article, “Hidden in plain sight: Observations on the origins of the Enneagram”:

“In recent years, the work of Evagrius has attracted the attention of the Enneagram community as it became clear that his map of eight thoughts that act as impediments to prayer match eight of the nine cognitive/emotional habits associated with the Enneagram personality styles… the parallels between the eight logisimoi of Evagrius and the passions of eight of the nine Enneagram types are unmistakable”(p 7).2

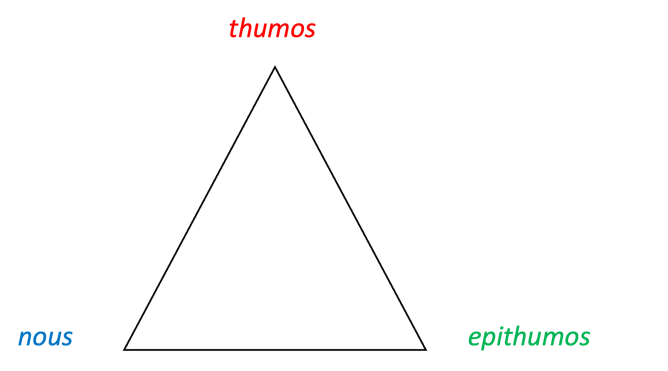

While it appears likely that Evagrius’s model does represent the roots of the contemporary Enneagram, his model of the human structure was not a typology of personality – he did not appear to think in terms of categorical differences among people. Instead, Evagrius’s model consisted of two interacting constructs3: a tripartite human soul made up of thumos, epithumos, and nous; and eight (or nine)4,5 logisimoi.

Stewart (2005) notes, “Although many earlier Christian writers mention the Platonic model of the soul and occasionally make use of its terminology, Evagrius is the first to make the model of nous, epithumia, and thumos central to his teaching on the Christian life” (p 19).6

Stewart goes on to explain, “… the tripartite model of the soul is far more evident than the schema of ‘eight generic thoughts’, suggesting that it is more fundamental to his ascetic pedagogy than the schema of eight logisimoi and the latter may even be derived from it” (p 19).7

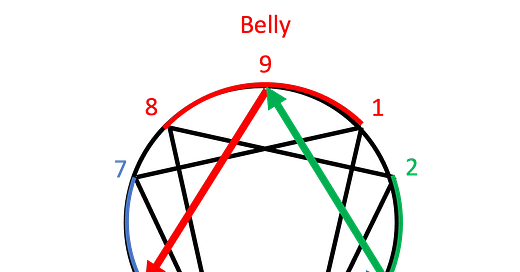

Placing Evagrius’s model of the tripartite soul on the Enneagram symbol

I think that Evagrius’s conceptualization of the human structure as comprised of thumos, epithumia, and nous is the precursor of the Enneagram centers construct. In very broad terms, for Evagrius and other Christian philosophers, thumos was associated with anger, epithumos was associated with desire, and nous was associated with thinking. A mapping of these characteristics of the parts onto the inner circle of the contemporary Enneagram would look like this:

I want to emphasize that I am not aware of any research showing that Evagrius ever represented his tripartite model in terms of a triangle with placement of thumos at the top, epithumos on the right and nous on the left. Rather, the diagram above is my own depiction of how I think Evagrius’s model of the soul would look when placed on the inner triangle of the contemporary Enneagram symbol.

Sense of Movement in Evagrius’s Model

In an earlier post I described an unusual feature of the Enneagram typology in which each type includes a unique pattern of movement among the three centers. In Evagrius’s model we can see, perhaps, the beginnings of this aspect of the contemporary Enneagram model.

For example, Evagrius writes:

“Of the (various types of) thoughts, certain ones lead, others follow. Those of the concupiscible lead, those of the irascible follow.

Of the thoughts that lead, some lead and some follow. The ones that lead are from gluttony, but the ones that follow are from lust.

Of the thoughts that follow, some lead and some follow. The ones that lead are from sadness, the ones that follow are from anger.” (Skemmata translated by W. Harmless and R. Fitzgerald (2001), (p 41 – 43)8

In another example of this sense of movement, Stewart (2005) observes, “Evagrius understands sadness…, as a reactive passion, caused by frustration of desire or following in the aftermath of explosions of anger” (p 27).9

Finally, Stewart (2005) touches on the possibility that Evagrius’s model included a description of how different logisimoi specialized in, or targeted, different parts of the tripartite soul, but notes evidence for this possibility comes from the work of John Cassian, one of Evagrius’s students, rather than from Evagrius’s own writing:

“The text from the Disciples of Evagrius suggests that Cassian may have learned the linkage between particular logisimoi and the parts of the soul from Evagrius himself. Given the pervasive role to the tripartite anthropology in Evagrius’s presentation of ascetic doctrine, associating the eight logisimoi with particular parts of the soul would have been an obvious move, though we have no extant text in which Evagrius does so” (p 30). 10

Importance of Evagrius’s Model to Contemporary Enneagram

I believe one of the most important aspects of Evagrius’s model is the depiction of human suffering understood in terms of what is internal to a human (the tripartite soul) and what is external to a human (the logisimoi).

As Gravier (2018) explains,

“The Aristotelian and Stoic traditions in particular emphasize the receptivity of the soul or mind in perception and thought. On this view, the world continually acts upon the mind, thereby providing it with specific content; perception and affect are thus not purely mental items, but states linking the perceiver with the world.

The permeability of the boundary between the self and the world is the main characteristic of pre-modern modes of self-constitution…. Greek doctors saw the human body as a system of channels that enable both external material and psychic matter to enter the body and pervade it… [there was an assumption] that the self is part of its surroundings, and that the dynamics that are at work in the cosmos are reflected in the human body… The conception of the human body as a small version of the universe blurs the boundary between internal and external causation” (p 60 - 61) (Italics added).11

This aspect of Evagrius’s work is important as it may be seen as a forerunner of the concept of three different forms of intelligence or intuition associated with the different centers.

Harmless, W. (2004). Desert Christians: An Introduction to the literature of early monasticism. Oxford University Press.

Wiltse, V and Palmer, H. (2011). “Hidden in plain sight: Observations on the origins of the Enneagram”. In The Enneagram Journal, Vol. Iv, Issue 1, pp 4 - 37.

Stewart, C. (2011). “Evagrius Ponticus and the Eastern monastic tradition on the intellect and the passions”. In Modern Theology, 27:2, pp 263 - 275.

Stewart (2005) notes, “Though these thoughts are mentioned frequently in all of Evagrius’s writings, the schema of eight logisimoi as such appears in only a few works; in one text he works with a list of nine.” (p 18). From “Evagrius Ponticus and the ‘Eight Generic Logisimoi’” in R. Newhauser, ed. In the garden of evil: The vices and culture in the Middle Ages. Toronto:PIMS, pp 3 -34.

Harmless and Fitzgerald (2001) provide a translation in which Evagrius writes, “The first thought of all is love of self (philautia); after [come] the eight” (p 511). They go on to note: “This assertion, that there is a ninth ‘thought’ prior to the others, is, to the best our knowledge, not found anywhere else in Evagrius’s writings” (p 511). From W. Harmless and R. Fitzgerald. (2011). “The Sapphire Light of the Mind: The Skemmata of Evagrius Ponticus” in Theological Studies, 62, pp 498 - 529.

Stewart, C. ibid, 3.

Stewart, C., ibid 4.

W. Harmless and R. Fitzgerald, ibid 5.

Stewart, C. ibid, 4.

Stewart, C. ibid, 4.

Gravier, I. (2018), Asceticism of the mind: Forms of attention and self-transformation in Late Antique monasticism. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, pp 60 - 61.