Claudio Naranjo (1932 - 2019) was a Chilean psychiatrist who studied with Oscar Ichazo. Naranjo’s work with Ichazo included deeply absorbing Ichazo’s model of the nine Enneagram types. Later Naranjo incorporated what he had learned during his time with Ichazo with a variety of other sources to create a theory and model of the Enneagram that proved to be a bridge between ancient and modern spiritual psychologies.1

Describing Naranjo’s contribution to the development of the Enneagram of personality, Helen Palmer wrote: “The difficulty with Ichazo’s Enneagram was that his précis was built on only one of the many dominant issues characteristic of a type, and his descriptive language did not readily translate into psychological terminology.” 2

Naranjo’s theory and model of the Enneagram results from his integration of many sources of information and knowledge.3 For the purposes of this project - understanding the Enneagram centers as a psychological construct - six elements of Naranjo’s Enneagram model stand out as most important:

Ichazo’s nine category typology of affective-cognitive distortions

Naranjo’s experience of the Enneagram types as depicting nine distinct structures of consciousness

Gurdjieff’s three category centers typology

The Buddhist three category “spiritual poisons” typology

Naranjo’s correlation of the nine personality structures with the structure of various personality disorders

Naranjo’s correlation of the nine personality structures with various defense mechanisms

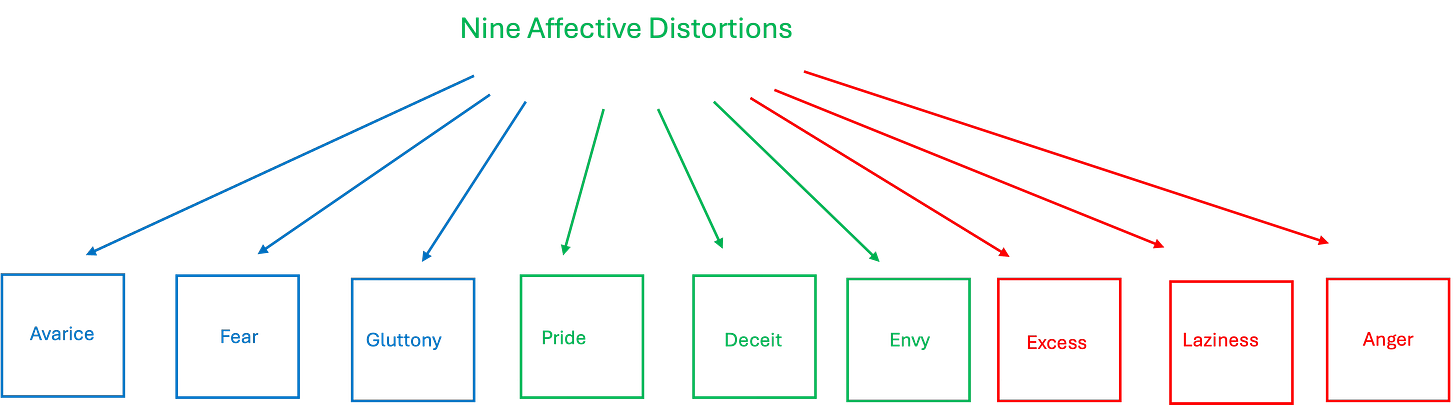

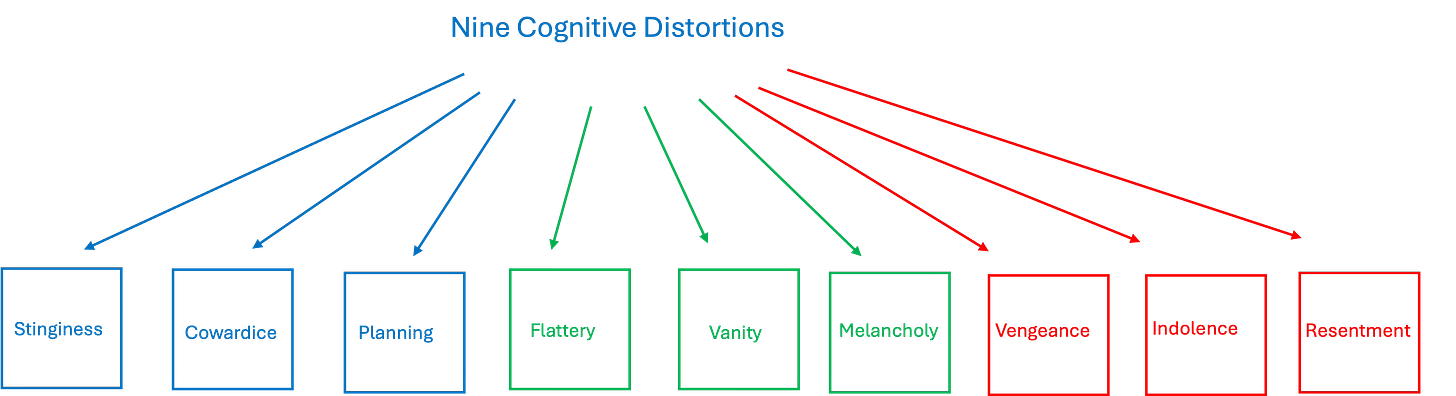

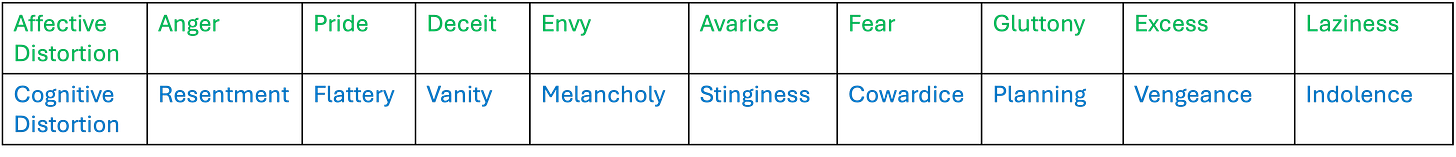

First element: Ichazo’s nine category affective-cognitive distortions typology

As we discussed in the previous chapter, Ichazo, similarly to Gurdjieff, conceptualized humans as tripartite beings consisting of three regions of the body with each region associated with a specific type of activity. But unlike Gurdjieff’s model of the human structure, Ichazo’s model did not categorize people in terms of which center was most predominate. Instead, Ichazo’s typology categorized people in terms of nine affective - cognitive distortions were most predominate in their personality. Though it included fairly vivid descriptions of how the nine distortions look and feel to self and other, the typology itself was sparse, with the categories being described in terms of just two elements.

Ichazo’s Nine Affective and Cognitive Distortions (Adapted from Lilly & Hart4 )

Ichazo’s Nine Category Affective-Cognitive Distortions Typology

Second element: Naranjo’s experience of the Enneagram types as depicting nine distinct structures of consciousness

Naranjo wrote that when he first heard Ichazo’s version of the Enneagram he experienced it as, “… a view of personality that seemed congruent with Gurdjieff’s but went beyond it in detail.” Later Naranjo studied with Ichazo in an intense small group setting. During this period Naranjo had an epiphany: “… I suddenly became able to see the structure of others’ personalities as a good caricaturist sees the essential traits in a person’s physical features”.5

Naranjo’s epiphany of the structural nature of the Enneagram types opened the door for him to begin thinking about the different parts that make up the structure, how those parts might develop, how the parts are kept in place, and what might allow the structure to dissolve. In other words, Naranjo began developing a theory of the Enneagram, and creating a model of the Enneagram that derived from this theory.

Third Element: Gurdjieff’s three category centers typology

As we have previously discussed, Gurdjieff conceptualized the human structure as being comprised of three centers. Each of Gurdjieff’s centers was associated with a particular region of the body - head, heart, or belly.

Gurdjieff’s Three Category Centers Typology (Adapted from Riordan6)

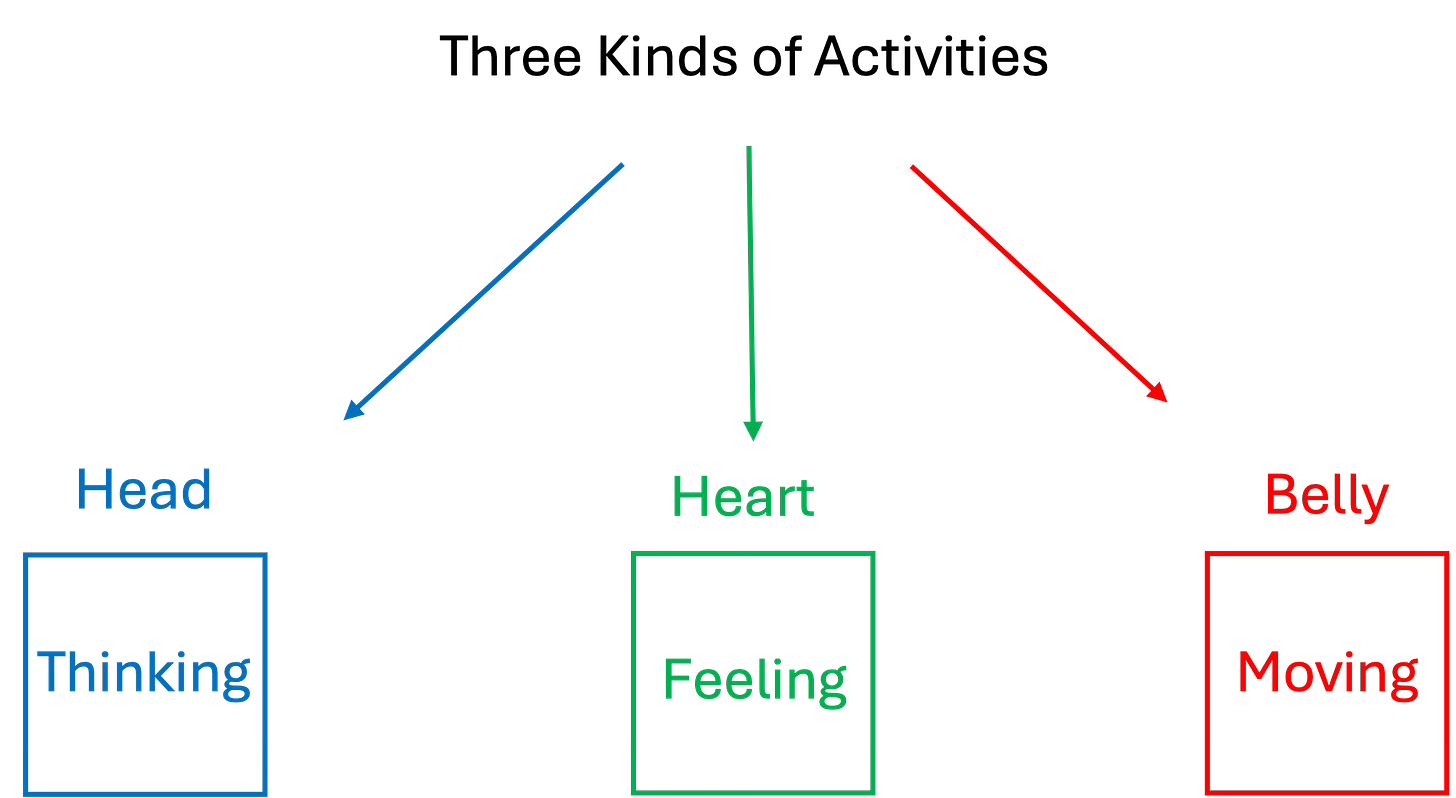

Like Ichazo’s nine category personality typology, Gurdjieff’s three category centers typology was thin, describing the centers in terms of just two elements: region of body and activity of that region.

The Gurdjieff’s centers typology was underspecified, but for Naranjo it served to highlight the fundamental role the activities of thinking, feeling, and moving have in creating and maintaining the nine affective-cognitive distortions described by Ichazo.

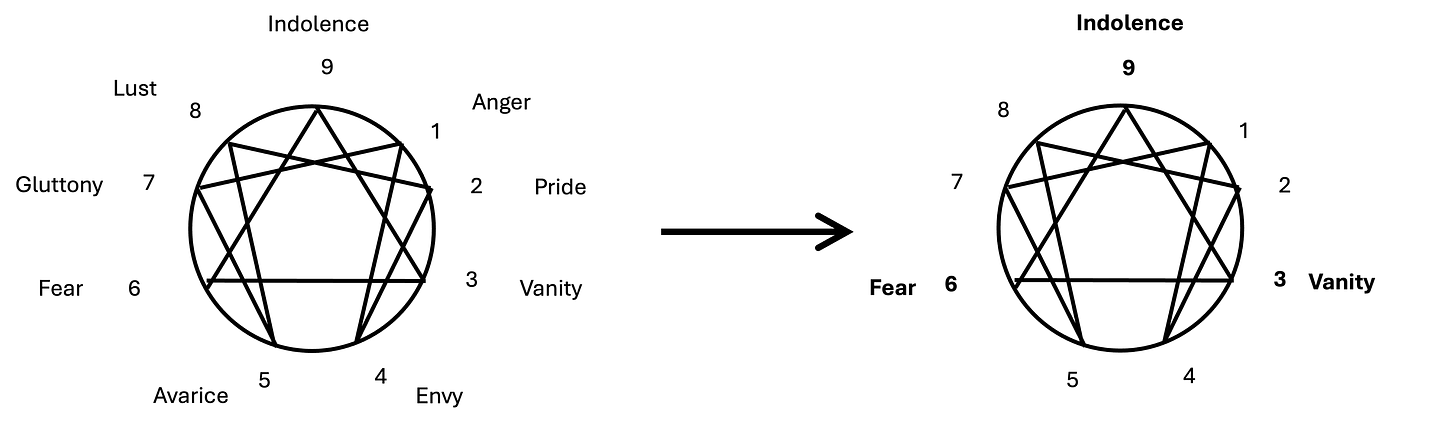

Naranjo wrote, “Inspection of the enneagram of the passions… shows that three of them (at points 9, 6, and 3) occupy a position more central than the others… The fact that these three mental states are mapped at the corners of the triangle in the enneagram of passions conveys a statement to the effect that they are cornerstones of the whole emotional edifice, and that the states mapped between them can be explained as interactions in different proportions of these three”.7

Personality theories can be thought of as focusing on one of three broad categories of human experiences. To paraphrase Murray8, in some ways each person is like all other people; in some ways each person is like some other people and unlike some other people; and in some ways each person is utterly unique.

McAdams and Pal9 point out that personality typologies are created and used in the branch of personality psychology that is interested in the middle category - the ways that each person is like some other people and unlike some other people.

Thinking about the nine Enneagram types in terms of Gurdjieff’s three category centers typology allowed Naranjo to begin seeing the nine Enneagram types from the perspective of theories of personality psychology that focus on categories of people. Naranjo began to see patterns related to how the three types in each center were similar to each other, and different from the types in the other centers.

Fourth Element: The Buddhist three category “spiritual poisons” typology

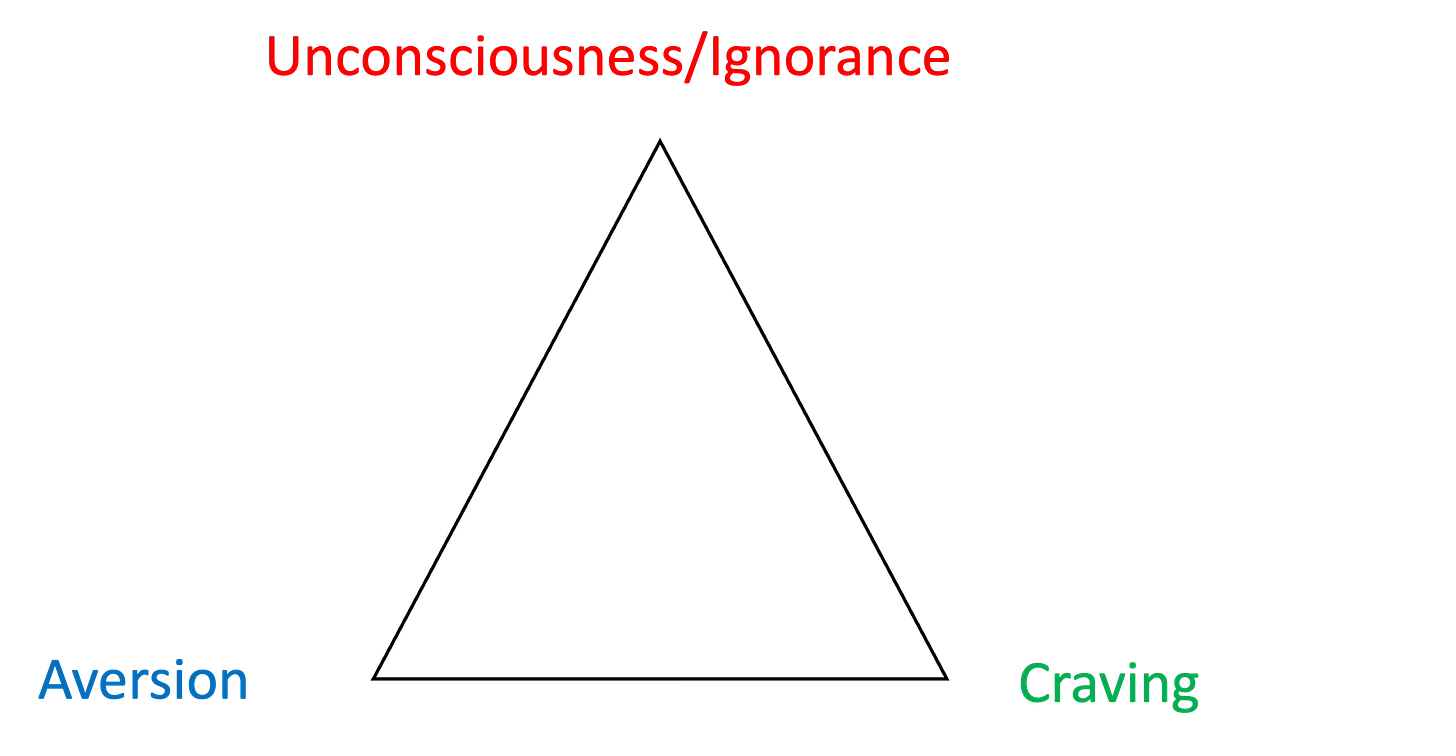

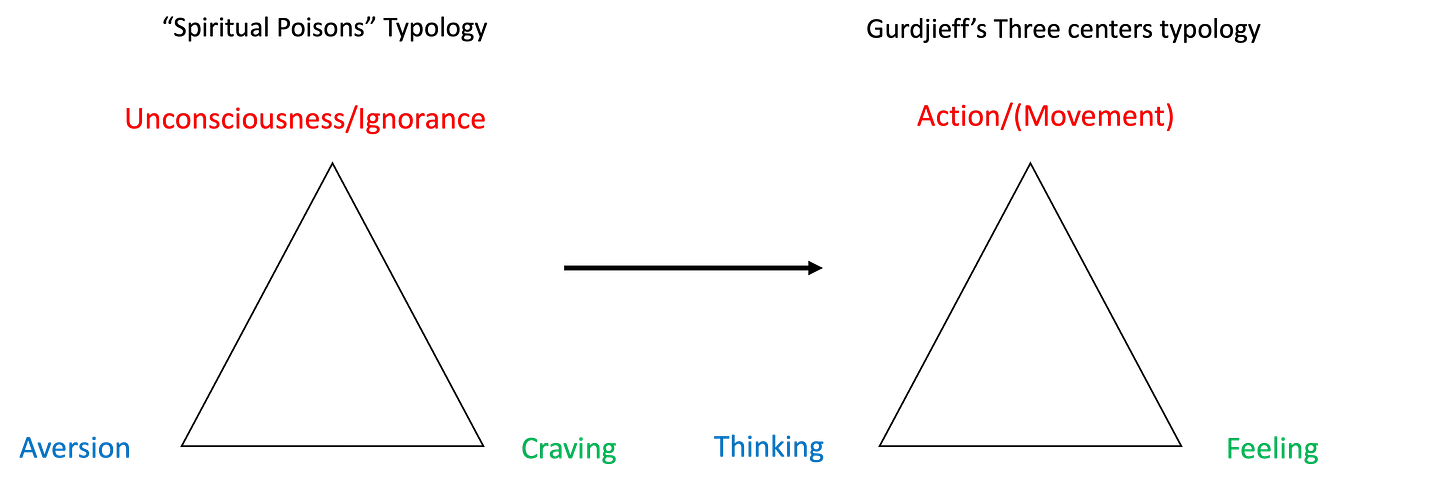

One of the patterns of variation Naranjo saw among the nine Enneagram types when he nested them into Gurdjieff’s centers typology reminded him of the Buddhist “spiritual poisons” typology.

Naranjo’s Mapping of the “spiritual poisons” typology onto the inner triangle of the enneagram symbol (Adapted from Naranjo10)

This comparison with the “spiritual poison” typology allowed Naranjo to describe the inner triangle in terms of, “… an interdependence of an active unconsciousness on one hand (commonly called ignorance in Buddhist terminology) and on the other a pair of opposites that constitute alternative forms of defining motivation: unconsciousness, aversion, and craving”.11

Naranjo’s Mapping of the spiritual poisons typology onto Gurdjieff’s centers typology (Adapted from Naranjo12)

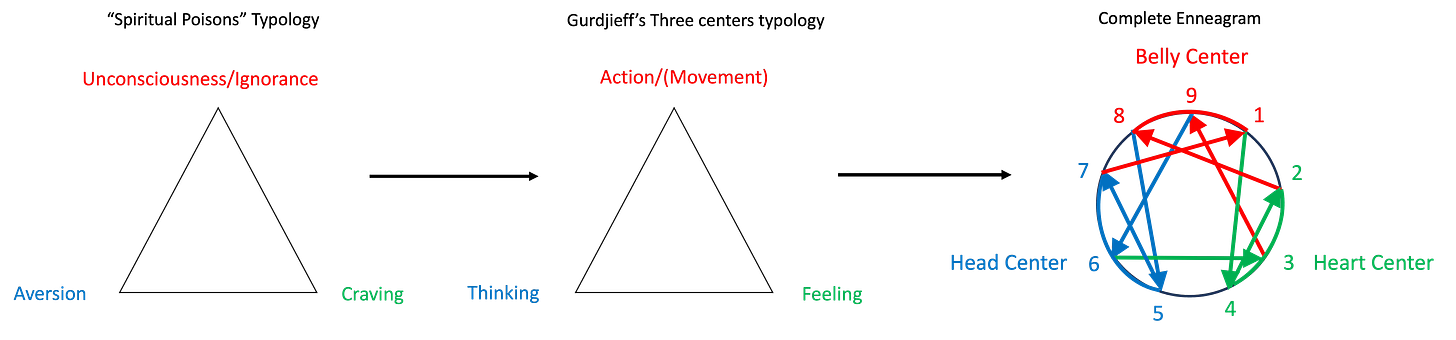

The integration of the spiritual poisons typology also allowed Naranjo to define the meaning of the Enneagram arrows, thus formalizing a core element of the contemporary Enneagram - that the the Enneagram symbol depicts unique patterns of movement for each type between and within the three centers.

As Naranjo saw it, “The relations indicated by the arrows connecting the points in the inner triangle of the enneagram, and also those connecting the rest of the points in the sequence 1, 4, 2, 8, 5, 7, 1 may be said to correspond to psycho-dynamic relations, when the enneagram is understood as a map of the individual’s mind..”.13

Naranjo’s Mapping of the integrated “spiritual poisons typology”/Head-Heart-Belly typology onto the complete Enneagram symbol (Adapted from Naranjo14 )

Fifth element: Correlation of the nine personality structures with specific personality disorders

In discussing personality disorders, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) first defines personality:

“Personality is the way of thinking, feeling, and behaving that makes a person different from other people. An individual’s personality is influenced by experiences, environment (surroundings, life situations) and inherited characteristics. A person’s personality typically stays the same over time.”

And then the APA defines personality disorders:

“To be classified as a personality disorder, one’s way of thinking, feeling and behaving deviates from the expectations of the culture, causes distress or problems functioning, and lasts over time… The pattern of experience and behavior usually begins by late adolescence or early adulthood and causes distress or problems in functioning. Without treatment personality disorders can be long lasting…”

The APA goes on to say that personality disorders can impact a person cognitively (how a person thinks about themselves and others); affectively ( a person’s emotional responses); interpersonally (how a person relates to others); and physically how a person controls their behavior).15

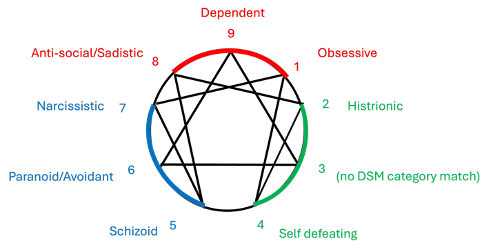

Thinking of the Enneagram types as nine different structures of consciousness, Naranjo saw that the descriptions of the Enneagram types had counterparts in the structures of personality disorders found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - III:

Naranjo’s mapping of personality disorders onto the Enneagram symbol (Adapted from Naranjo16 )

Naranjo recognized that for each Enneagram type there is a continuum of distress caused by the activity of the personality. At the low end the activity of the personality is almost imperceptible; at the high end the activity of the personality results in personality disorders. Most people are usually functioning at some point along this continuum.

Naranjo wrote: “While in the case of each one of the ennead-types we find that it coincides with a known clinical syndrome, it is also true that everybody may be regarded as the bearer of one personality orientation or another, and that each may be seen in specific levels ranging from that of psychotic complication to that of the subtle residues of childhood conditioning in the life of saints.”17

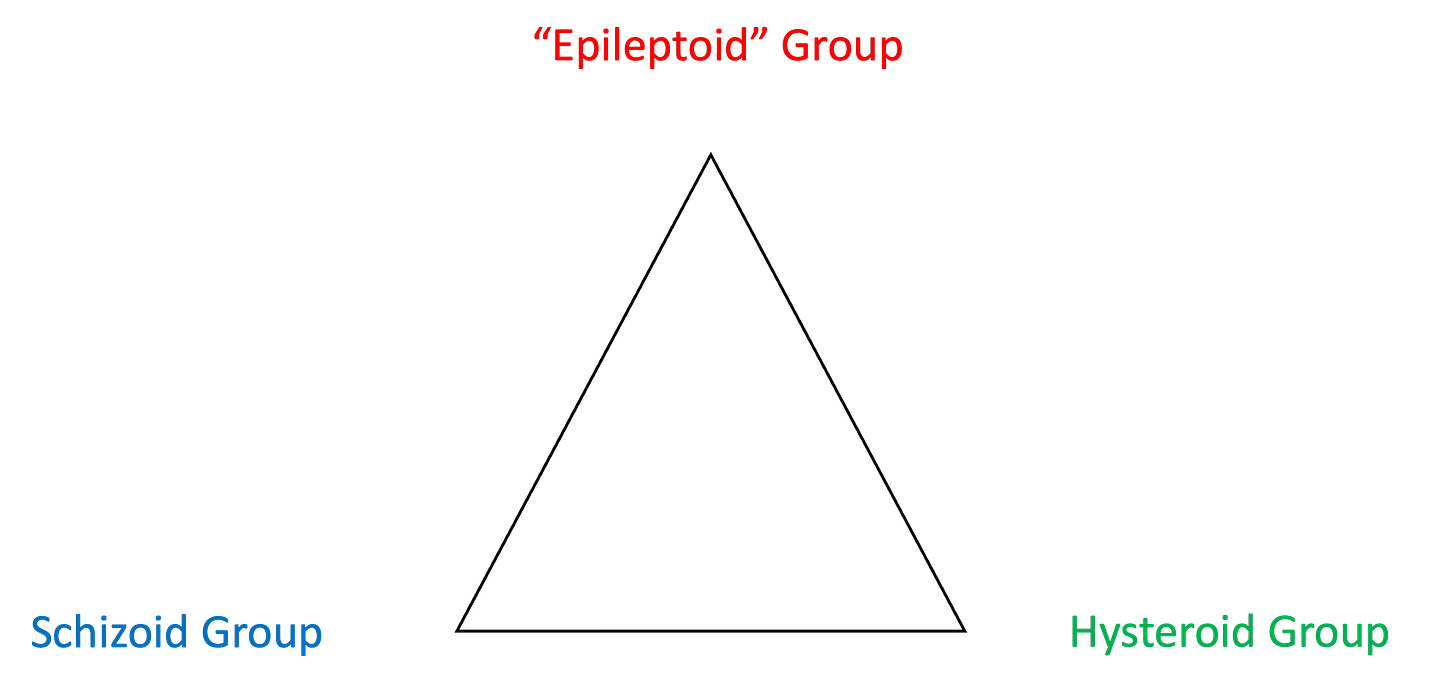

Thinking of the Enneagram types in terms of personality disorders, and focusing on the personality characteristics of the core points 3, 6, and 9, Naranjo thought that the three centers varied in terms of the kind of personality disorders they were associated with in his model of the Enneagram.

Naranjo wrote, “Agreeing… with current opinion in terms of the grouping of DSM III syndromes, the present characterology recognizes three fundamental groups: the schizoid group, with and orientation to thinking… the hysteria group, with an orientation to feeling… and another group (which Krestchmer might have called collectively epileptic) the members of which are… predominately oriented to action”.18

Naranjo’s three category typology of personality disorders mapped onto the inner triangle of the Enneagram symbol (Adapted from Naranjo19)

Naranjo’s mapping of his own personality disorder typology onto the Gurdjieff’s centers typology (Adapted from Naranjo20 )

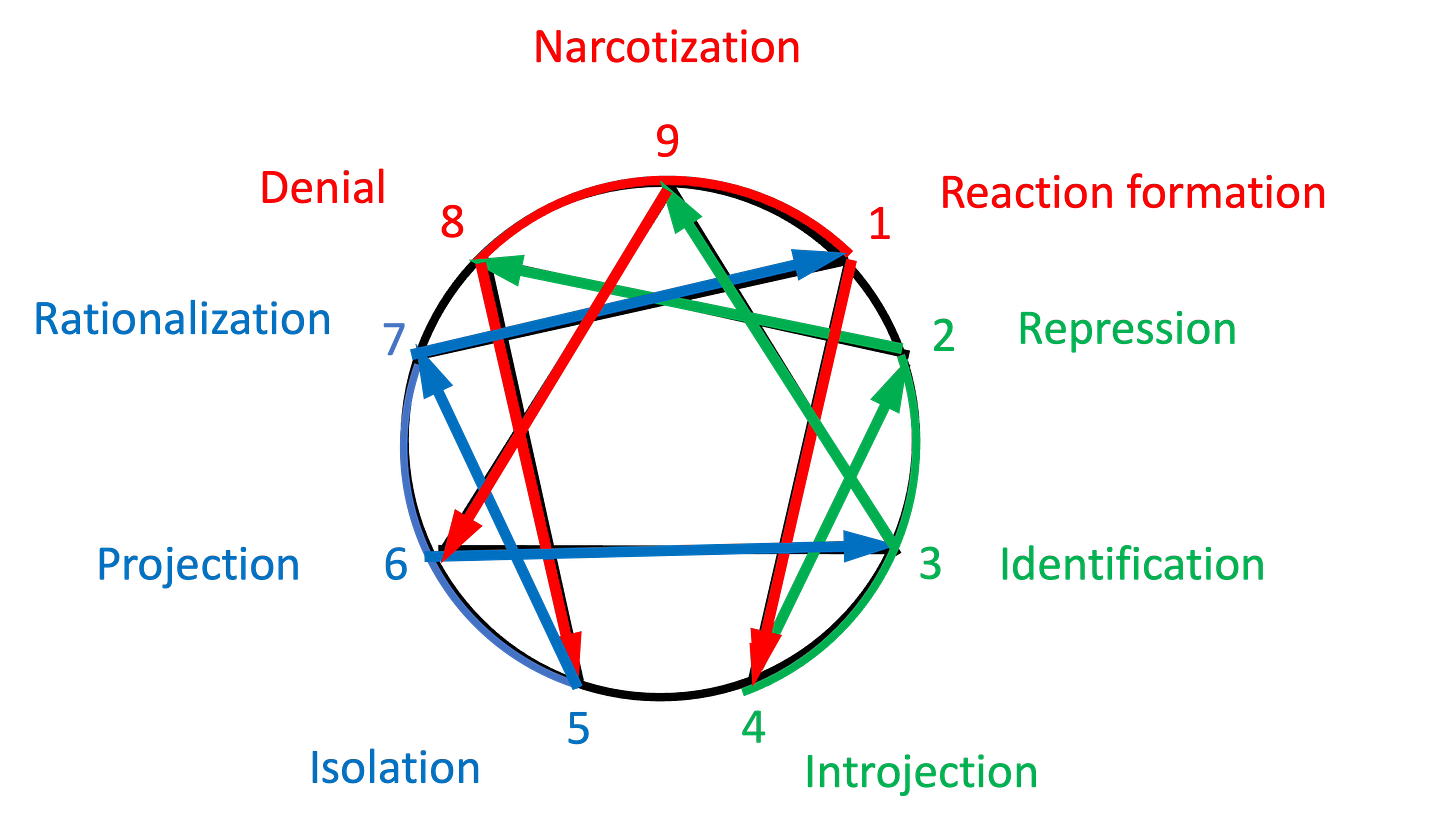

Sixth element: Correlation of the nine personality structures with specific defense mechanisms

Granieri et al. (2017) define defense mechanisms as, “… unconscious mental mechanisms that are directed against both internal drive pressures and external pressures, especially those that threaten self-esteem or the structure and the integration of the self; they are part of normal personality functioning; they can lead to psychopathology, if one or more are used excessively; they are distinguishable from one another.”

In Naranjo’s model, defense mechanisms play a crucial role in maintaining the structure of the Enneagram type. As Naranjo explains, “Out of a personal conviction concerning the importance of the cognitive domain I have paid special attention to the subject of defense mechanisms (i.e., the selective ways of sustaining unconsciousness) that may be regarded as interdependent with the different interpersonal styles…”.21

Naranjo’ Mapping of defense mechanism onto Enneagram (Adapted from Naranjo22)

I am not aware of Naranjo explicitly discussing the Enneagram defense mechanisms in terms of core characteristics of the Enneagram centers, but his modeling of the Enneagram certainly invites us to think about the possibility that the defense mechanisms of the core points 3, 6, and 9 may be generic and inter-related, and the defense mechanisms of the wing points in each center may be variations of the core defenses.

Summary

Naranjo’s Enneagram yields a description of the centers from the perspective of psychodynamic and personality psychology theory and research. In addition to integrating the work of Gurdjieff and Ichazo, Naranjo’s model also includes descriptions of how the centers vary in terms of directional orientation of consciousness and type of personality disorder. Naranjo’s integration of his own personality disorder typology invites us to think about the possibility that there are three core defense mechanisms, each with two variations.

Palmer, H. (1988). The Enneagram: Understanding yourself and the others in your life. HarperCollins, p 51.

Palmer, H. ibid, p 51.

Naranjo, C. (1994). Character and neurosis: An integrative view. Gateways/IDHHB, Inc.

Lilly, J. and Hart, J. (1975). “The Arica Training”. In C. Tart (Ed.), Transpersonal Psychologies, Harper & Row, pp 329 - 351.

Naranjo, C ibid, p 22.

Riordan, K. (1975). “Gurdjieff”. In Transpersonal Psychologies, C. Tart (Ed.), Harper & Row, pp 281 - 328.

Naranjo, C. ibid, p 50.

Kluckhohn, C. & Murray, H. (1953). “Personality formation: The determinants”. In C. Kluckhohn, H, Murray, & D. Schneider (Eds.), Personality in nature, society, and culture , Knopf, pp 53 - 67.

D. McAdams & J. Pals, (2007). “The role of theory in personality research”. In R. Robins, C. Fraley, & R. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology, The Guilford Press, pp 3 - 20.

Naranjo, C. ibid, p 33.

Naranjo, C. ibid, p 32.

Naranjo, C. ibid, p 32 - 33.

Naranjo, C. ibid, p 47.

Naranjo, C. ibid.

“What are Personality Disorders?” American Psychiatric Association, psychiatry.org.

Naranjo, C. ibid.

Naranjo, C. ibid. p. 44.

Naranjo, C., ibid p. 43.

Naranjo, C. ibid p 43.

Naranjo, C. ibid.

Naranjo, C. ibid p. 26.

Naranjo, C. ibid.