Introduction

Helen Palmer had training in psychology and Zen meditation and was studying and teaching intuition practices in Berkeley, California when she learned about the Enneagram from Claudio Naranjo in the 1970s. Palmer had been teaching her students attention management practices as part of their intuition training and she was intrigued by the patterns of attention that Naranjo’s students described as they shared narratives about their Enneagram types.1

Palmer wrote:

“The [Enneagram] system was being developed as an esoteric psychological tool. My own interests were in the areas of spiritual practice and intuition training, rather than psychology, but I wanted to see if people of the same type were attracted to similar meditation practices, and I wanted to uncover typical practice problems that each type was likely to encounter. My moment of truth came on Five night (the Observer). Naranjo was interviewing a group of Fives about their early family life, and one highly contracted Observer type, who sat for the entire night perched high up on the arm of a sofa, watching the action from a safe distance, said something like, “I knew what my family wanted to get from me before they knew it themselves.

I remember feeling suddenly relieved and grateful. The Five’s casual remark had fallen on an awareness that had been developing in me for a long time, and his physical presence, coupled with what he said, was the trigger that drew me to the Enneagram. I knew immediately that he was intuitive in that one area, that his sensitivity had developed as a part of his childhood survival strategy, and that he was probably astute enough to describe how he altered his perceptions to ‘know other people’s expectations’,

and that if he could clarify to himself what he was already doing in that one small, defensive area of his life, he would have a good chance of gaining voluntary access to an intuitive state of mind.”2

This quote from Palmer captures three key concepts of Palmer’s model of Enneagram type development.

Like Naranjo, Palmer thought of the Enneagram types as developing out of the need to navigate close family relationships in childhood.

Palmer saw a developmental connection between the unconscious, involuntary attention patterns mapped by the Enneagram and the capacity in adulthood to learn how to consciously and voluntarily access intuitive states.

The connection between the unconscious deployment of attention of the Enneagram types and the conscious training of various intuitive states is mediated by an “inner observer”.3 and the ability to recognize and work with the inner observer can be developed with practice.

Palmer’s Theory of Type Development

Naranjo’s model of the Enneagram conceptualized the types in terms of neurotic styles that develop in early childhood in the context of the family environment. Palmer extended and refined Naranjo’s model of the Enneagram by focusing on the role attention styles play in the development and maintenance of the Enneagram type structure.

Both Naranjo and Palmer saw the types as developing in early childhood in the context of the family environment. However, Palmer’s model provides a description of the mechanisms underpinning the neuroses that Naranjo’s model highlights.

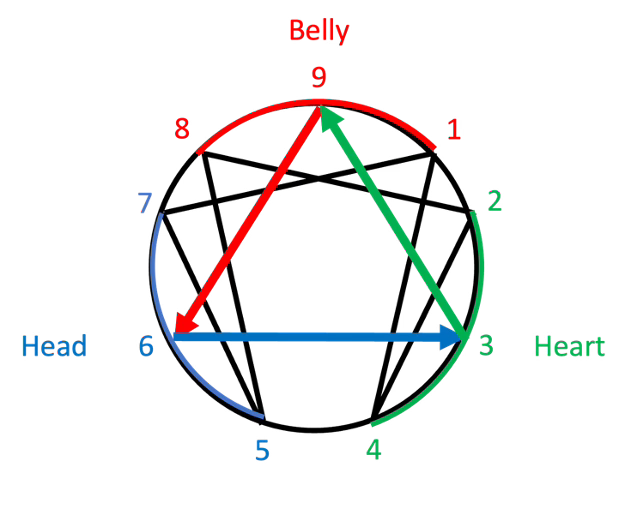

Palmer’s Centers Typology

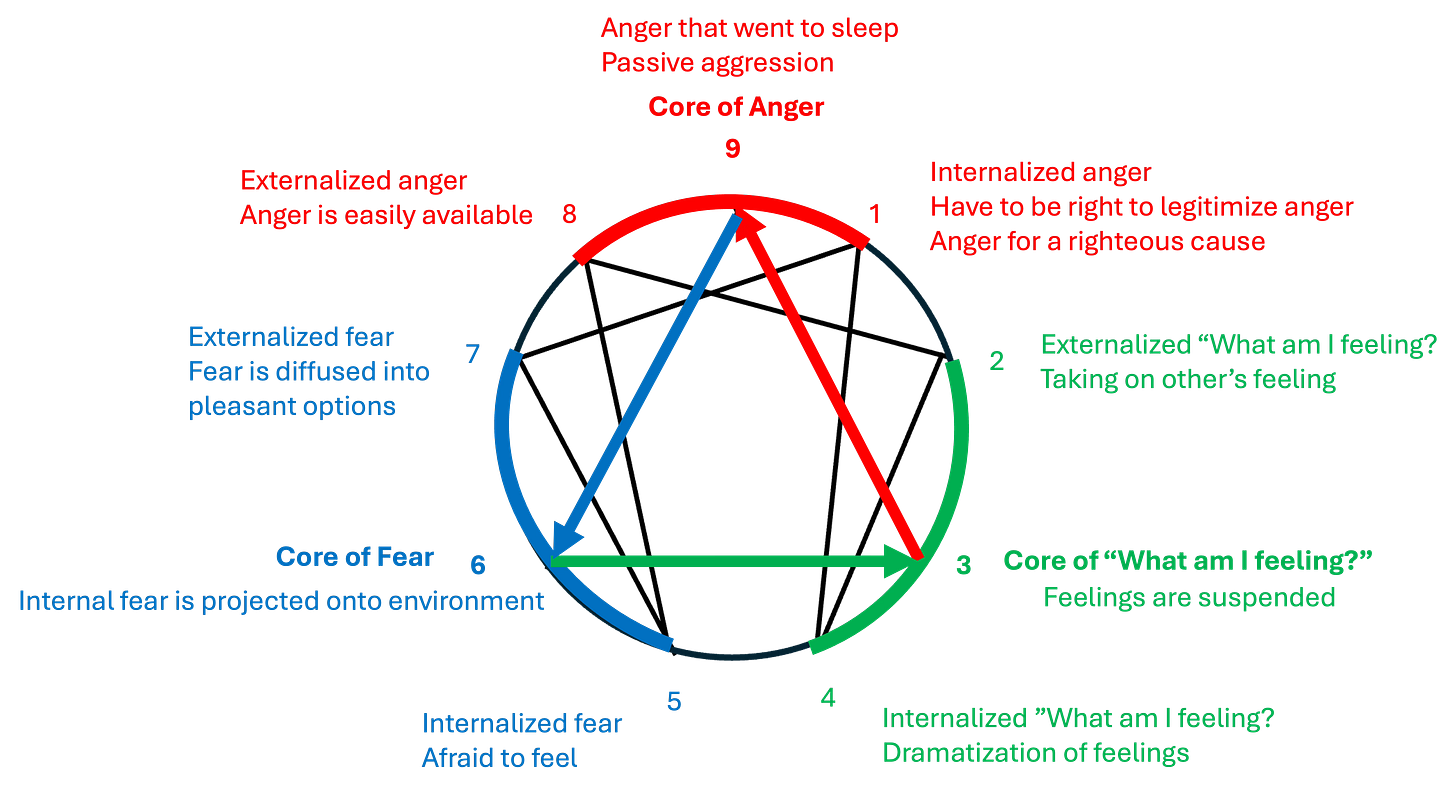

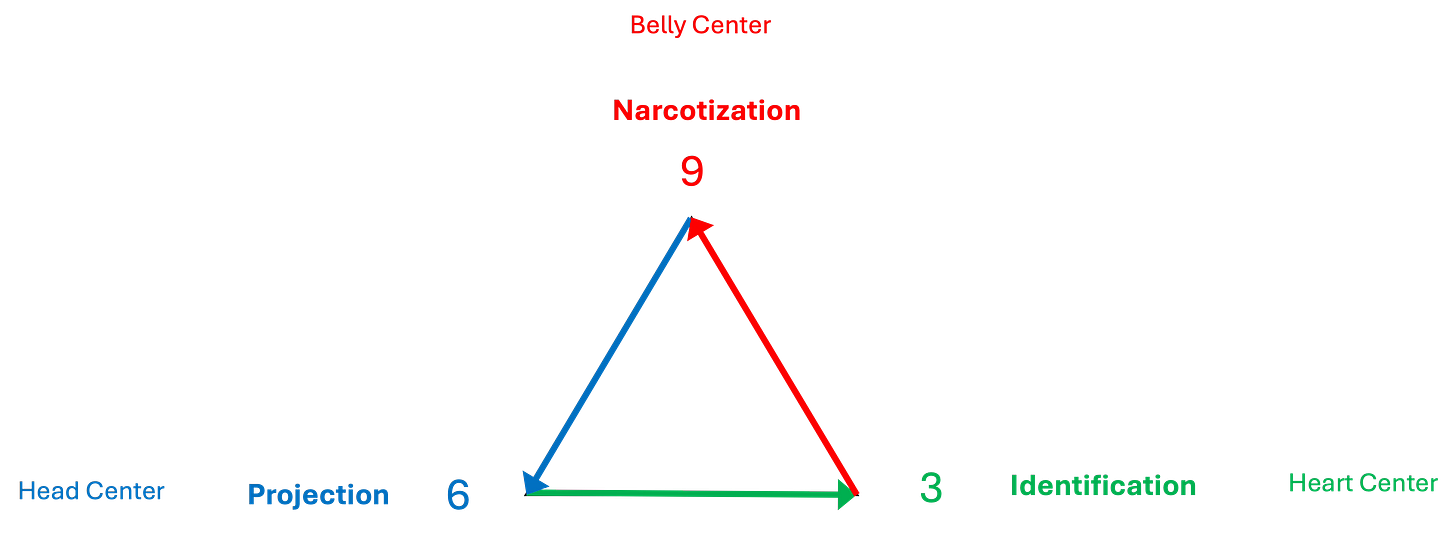

Palmer’s Centers typology also expands on Naranjo’s insight that the characteristics of the core points (Three, Six, and Nine) are related to the characteristics of the other two points in each center. Palmer explains this part of her model in her discussion of the Enneagram wings – the two points on either side of the core point in each center:

“The points that appear on either side of the Three-Six-Nine triangle are variations of the core personalities. That means that the two wing points of Three, which are Two and Four, share a common preoccupation with image and also live out variations of the question ‘What am I feeling?’. The wings of Six (Five and Seven) share an underlying paranoia, as well as emotional habits of fear. The wings of Nine (Eight and One) share a core predisposition toward the sleep of self-forgetting, which is the forgetting of personal priorities, as well as a predisposition toward anger.

The wings of the Three-Six-Nine triangle represent an externalized and internalized version of the core preoccupations… [for example] a Seven (externalized fear type), looking initially not at all afraid, would be likely to become more overtly furtive and paranoid (core of Six) as psychological defenses weaken.

Only the Three-Six-Nine triangle points show an external and internal version of themselves at the wings. For example, the wings of Eight, which are Seven and Nine, do not represent an externalized and internalized version of Eight. The wings of any point are influential, however, because they give a flavor to that personality type. For example, in the anger group at the top of the Enneagram, a Nine, who will prefer to express anger indirectly and passively, will lean either to the Eight side (the Boss), making for a blunt and stubborn ‘don’t push me’ kind of passive anger, or to the One side, (the Perfectionist), making for a nitpicking criticality, which will still be acted out in indirect ways.

Likewise, someone with a noncore point, such as Four (the Tragic Romantic), who expresses feelings in a dramatized way, will lean either toward Five (the Observer), in an internalized depressive stance, or toward Three (the Performer), in a more hyperactive effort to keep melancholia at bay. The flavors to the wings help to make each personality highly distinctive. No two people who belong to the same type are identical, although they share the same preoccupations and concerns…. A fiveish Four would be a more withdrawn and private kind of Four, whereas a threeish Four would be a more flamboyant, dramatic Four, who maintains an active schedule, but still relates to the Four stance of melancholy, sadness, and loss. Each type is affected by both of its wings, and although the flavor of one of the wings will predominate in the personality, it would be improper to discount the fact that the other exists as a potential”.4

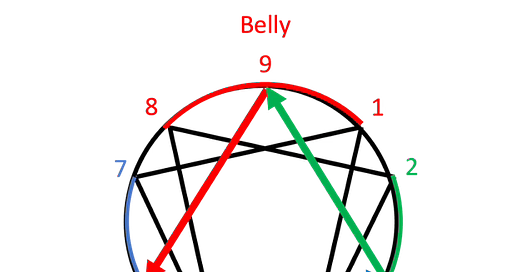

In the above quote, Palmer is describing a key component of her Centers typology. In this typology, the three types within each center vary in terms of their habitual intrapersonal orientation of their attention (away from self, towards self, or neutral). This intrapersonal orientation of attention component is depicted below5

Other key components of Palmer’s Centers typology

In addition to the intra-personal orientation of attention component discussed above, there are seven other key components in Palmer’s centers typology.

Habitual focus of attention6

Blind spot7

Interpersonal orientation of attention (towards - away - against)8

Defense mechanism9

Pathology10

Affective-cognitive preoccupation11

Intuitive style12

Summary

Palmer’s Centers typology defines the three centers as three different attention structures, each organized around a distinct habitual focus of attention.

Each center has an interpersonal orientation of attention with the Head center types (5, 6, and 7) holding a moving away orientation, the Heart center types (2, 3, and 4) holding a moving towards orientation of attention, and the Belly center types (8, 9, and 1) holding a moving against orientation of attention.

Within each center each type varies according to whether their intrapersonal orientation of attention is habitually directed away from self (types 2, 7, and 8), towards self (types 1, 4, and 5) or neutrally (types 3, 6, and 9).

As a person’s situation changes, attention moves according to the unique pattern of each type. When attention moves to a different center or to a different position within the same center (depending on the particular type’s pattern), the person’s attention structure changes, for as long as they are in the different center, or different point within the center.

The blind spot and defense mechanism components of the typology can be understood as interlocking mechanisms that function to keep the attention structure in place. The affective-cognitive preoccupation component can be understood as resulting from the continuous attention on the habitual focus of attention. The pathology component of the typology can be understood as resulting from an overly rigid pattern of attention in which the person is unable to shift out of their own state enough to see things from alternative perspectives. The intuitive style component can be understood as the opposite of the pathology component, in which the person is able to fully experience alternative perspectives, while still having access to their own perspective.

******

The French philosopher Simone Weil wrote, “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.”13 By providing such a detailed map of the unconscious, involuntary patterns of attention of each type, Palmer’s model functions as a tool for learning how to bring unconscious states of attention to consciousness.

It is in these states of consciousness, however brief they may be, that we are able to share with ourselves and others the rare gift of pure attention that Weil describes.

Miller, D. “The politics of radical clarity: Helen Palmer and the Enneagram” in The Sun, October 1988.

Palmer, H. (1988). The Enneagram: Understanding yourself and the others in your life. HarperSanFrancisco, pp 52 - 53.

See Siegel, D. (1999). The Developing Mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. The Guildford Press, pp 324 - 326, for a discussion of the role of the inner observer in child development.

Palmer, H. ibid 2, pp 41 - 43.

Adapted from Palmer, H. ibid 2, p 42.

Adapted from Palmer, H. (1988). The Enneagram: Understanding yourself and the others in your life. HarperSanFrancisco, p 52.

Adapted from Palmer, H. and Brown, P. (1998). The Enneagram advantage: Putting the 9 personality types to work in the office. Harmony Books.

Palmer discusses this aspect of her model in an interview on Conscious TV

Palmer, H. ibid 2, p 54.

Palmer, H. ibid 2, p 62.

Palmer, H. ibid 2, p 38.

Palmer, H. ibid 2, p 56.

Weil, S. (1942). In S. Pétrement Simone Weil: A Life (19760 tr. Raymond Rosenthal