Over the past year I have reviewed six models of the Enneagram in an attempt to develop a better understanding of the Enneagram centers. What stands out to me most starkly as I come to the end of this phase of my project is the lack of agreement across the models about the core qualities of the Heart center.

Beatrice Chestnut flagged this controversy years ago in her series on the Heart center for Nine Points Bulletin. Framing the issue as a question of core emotions Chestnut wrote, “For some time now I have been thinking about the fact that while most in the Enneagram community seem to agree that anger and fear represent the core emotions associated with the body types and head types… there appears to be a lack of consensus about the core emotion connected to the heart types”.1

Why does lack of agreement matter?

To me, the lack of agreement about the qualities of the Heart center signals that there is still more for us to learn and understand about the Enneagram personality typology.

As I wrote in my dissertation on Enneagram types and adult attachment styles, “Typologies are cultural constructions that allow for the categorization of objects according to relevant variables. Humans construct typologies because they are useful tools for gathering, comprehending, and applying information about complex systems, including humans systems…. Personality typologies are used in MFT [Marriage and Family Therapy] and other branches of psychotherapy because some clinicians find that they increase the effectiveness of the therapeutic process… When typologies are useful, they reveal patterns of characteristics that would not be visible in the absence of the categorization. This emphasis on patterns of interacting variables is particularly important when complex systems such as individuals, couples, and families are the subject of investigation, because change in these systems [is] often non-linear, and cannot be fully understood using non-systemic approaches” (emphasis added).2

Looking back at this quote now in the context of my recent immersion in the literature of Enneagram center typologies, the issue of relevant variables takes on even greater importance for me than when I first wrote about it over fifteen years ago.

All the models that Chestnut reviewed in her series for Nine Points and those that I have just finished reviewing for my own project can be understood as categorizations of relevant variables. Beginning with Evagrius (arguably) and stretching all the way to the most recent model presented by the PDP Group in 2024, Enneagram theorists have been observing human patterns of thought, affect, and behavior and organizing their observations into a nested typology of nine individual categories (the Enneagram types, or patterns) grouped into three larger categories (the Enneagram centers, or triads).

Especially in terms of the Enneagram centers however, the models have varied in their selection of the variables to be categorized. This lack of agreement about what is being categorized in each center is most notable in each model’s description of the Heart center.

The table below compares the centers models covered by Chestnut’s series and my own review. Models marked by one asterisk were covered in my review; models marked by two asterisks were covered in both my review and Chestnut’s series.34

The Need for a Rapprochement

To me, the lack of agreement across these models about the qualities of the Heart center means that we still lack a clear understanding of, and by extension the ability to operationalize5, the Enneagram centers. This lack of a coherent construct is an impediment to research on the Enneagram personality typology and may also affect the clinical usefulness of the Enneagram.

I believe the Enneagram model that I am currently developing, which builds on my 2008 model6 based on adult attachment styles, provides the possibility of a rapprochement amongst these widely divergent conceptualizations of the Heart center while also pointing the way towards operationalization of the centers construct.

I will be describing my model in detail in the next phase of this project. For now, here is a quick sketch of what I am working on.

The Enneagram of Mentalization Styles

My model of the Enneagram draws primarily on two fields of research, both of which are grounded in Attachment Theory. The first field concerns the development and functioning of attachment processes ; the second field concerns the development and functioning of mentalization processes.

Three interrelated behavioral systems

The attachment processes literature provides a model of the development and functioning of three interrelated behavioral systems: the Attachment system, the Caregiving system, and the Power system. The Attachment system functions to establish, monitor, and repair close relationships and has been shown to vary in theoretically predicted ways influenced, in part, by an individual’s original attachment experiences.78 The Caregiving system is described as developing in the context of childhood attachment relationships and functions to facilitate the provision of care to others in need.9 The Power system also develops in the context of early attachment relationships and functions to allocate attention and energy towards and away from self and other, depending on the situation.10 Like the Attachment system, both the Caregiving and the Power systems have been shown to vary at the individual level in theoretically predictable ways associated with adult attachment styles.1112

The diagram below depicts my mapping of these three behavioral systems onto the Enneagram symbol.

Three modes of imagination supporting the capacity to mentalize

The mentalization processes literature provides a model of three interrelated modes of imagination13 that function to support the human capacity to mentalize, that is, the capacity to experience the self and others as intentional beings who can be understood in terms of ever changing mental states.14

Humans constantly shift back and forth among these three modes as internal and external circumstances change. However, there also appear to be different patterns of rigidity in flow between these states that are associated with personality disorders.15

As Bateman et al. (2023) explain, “We have argued that vulnerability to mental health disorders is the flipside of the advantages that mentalizing brings… whatever the neural systems are that underpin mental disorder, they must have other functions that are critical for survival. A defining feature of mental disorder is the experience of ‘wild imagination’, and we consider that mentalizing difficulties – the tendency to get caught up in unhelpful ways of imagining what is going on both for ourselves and other people – are the price we pay as a species for the immense benefits of human imagination.”16

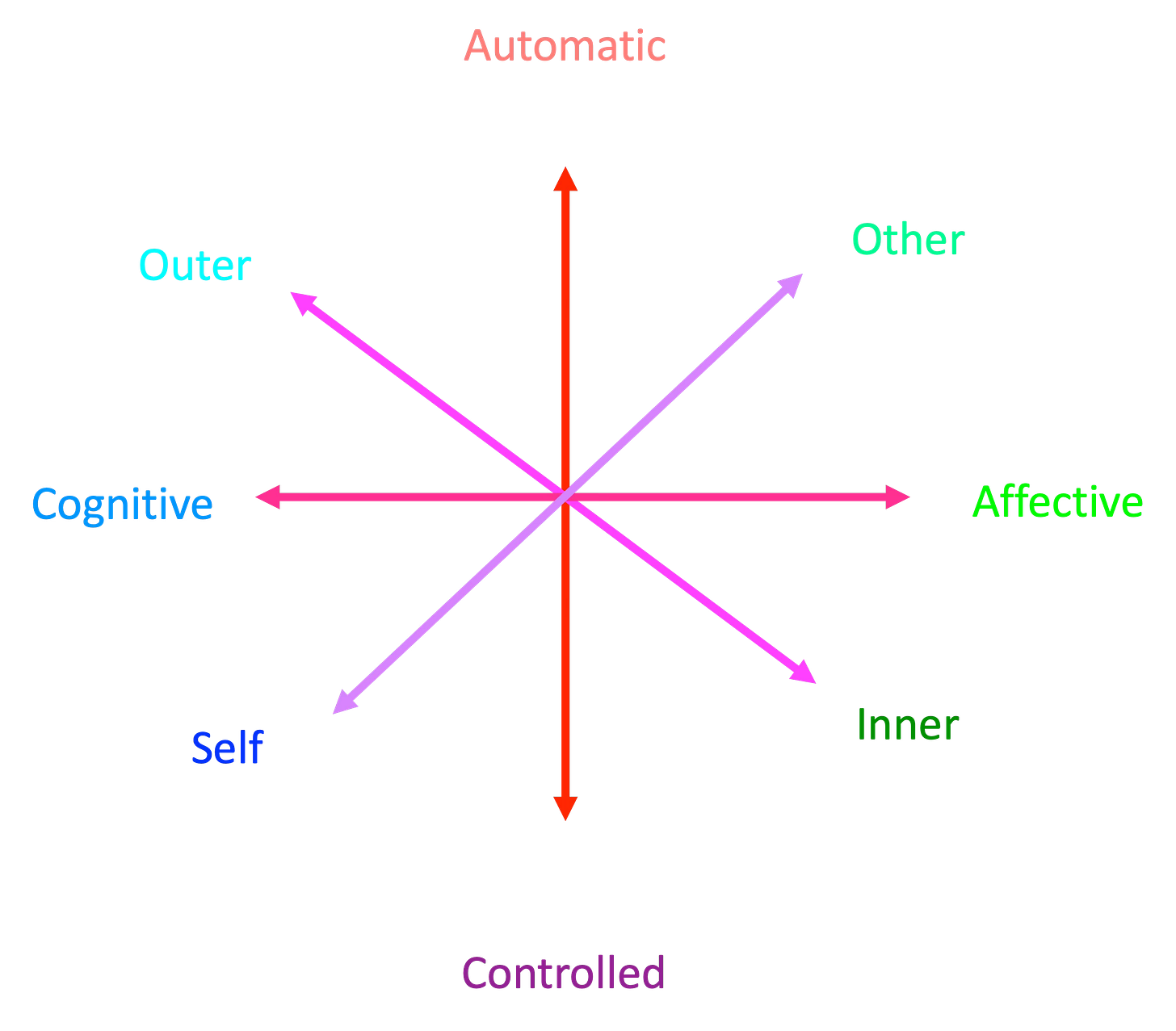

The diagram below depicts my mapping of the three imagination modes onto the Enneagram symbol.

Four dimensions of social awareness supporting three modes of social imagination

Finally, the three modes of imagination that combine to allow humans to experience self and others as intentional beings are thought to emerge from neurological processes that allocate attention along four dimensions. 17

The four dimensions are:

Automatic versus Controlled

Cognitive versus Affective

Mentalizing about self versus mentalizing about other

Mentalizing based on internal cues versus mentalizing based on external cues

Conclusion

The model of the Enneagram that I am developing conceptualizes the Enneagram centers in terms of three interrelated behavioral systems.

I am proposing that the functioning of these behavioral systems is supported by three modes of imagination that allow humans to accurately experience and understand self and others as intentional beings. These three forms of imagination emerge from a neurological substrate that allocates attention along four dimensions.

I am proposing that these three modes of imagination with their supporting neurological activities can be understood as contributing to the functioning of the three behavioral systems described above, and taken together constitute the core relevant variables of the Enneagram centers.

Chestnut, B. (September, 2009). “Shame, envy, feelings, hysteria, or sadness?: Locating the core emotion of the heart types”. Nine Points Bulletin, International Enneagram Association, p 1.

Arthur, K. (2008). Attachment styles and Enneagram types: Development and testing of an integrated typology for use in Marriage and Family Therapy. Dissertation, Virginia Tech.

Criteria for choosing models included in Centers Comparison Table

I chose the six models covered in my review because I believe that these models represent significant points of change in the development of the Enneagram centers construct.

In contrast, Chestnut sought to include as many voices as possible in her review of the Heart center construct. Chestnut’s series included several authors who responded to her call for opinions with statements that were in agreement with one of the models already covered in the series. I did not include these follow-up responses in this table. Additionally, Chestnut included a transcript of an interview with a former student of Ichazo’s that Chestnut noted seemed to be about a “different enneagram system”. Information from this interview has also not been included in the table.

Sources for Centers Comparison Table

Riso, D. (1987). Personality types: Using the Enneagram for self-discovery. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Palmer, H. (1988). The Enneagram: Understanding yourself and others in your life. Harper & Row.

Naranjo, C. (1989). Character and Neurosis: An integrative view. Gateways/IDHHB, Inc.

Riso, D. & Hudson, R. (1989). The wisdom of the Enneagram: The complete guide to psychological and spiritual growth for the nine personality types. Random House Publishing Group.

Jaxon-Bear, E. (2001). The Enneagram of liberation: From fixation to freedom. Leela Foundation.

Burke, D. (November 2009). “Locating the core emotion of the Heart types: Historical and biological substantiation of envy as a universal emotion”. Nine Points Bulletin, International Enneagram Association, p 13.

Chestnut, B. (2008). “Understanding the development of personality type: Integrating Object Relations Theory and the Enneagram system”. The Enneagram Journal, International Enneagram Association, pp. 22 - 51.

Killen, J. (2009). “Toward the neurobiology of the Enneagram”. The Enneagram Journal, International Enneagram Association, pp. 40 - 61.

Hall, D. (January/February 2010). The core emotions of the centers: An evolutionary perspective”. Nine Points Bulletin, International Enneagram Association, p 5.

Siegel, D. & the PDP Group (2024). Personality and wholeness in therapy: Integrating 9 patterns of developmental pathways in clinical practice. Norton Professional Books.

Da Boeck, P. et al. (2024). Questioning psychological constructs: Current issues and proposed changes. Psychological Inquiry, 34(4), 239 – 257.

Arthur, K. (2008). Ibid, 2.

Mikulincer, M. & Shaver, P. R. (2016). “Adult attachment and emotion regulation”. In J. Cassidy and P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications, 3rd edition (pp. 507 - 533). Guilford Press,

Arthur, K. ibid 2.

Shaver, P.R. , Mikulincer, M., & Shemesh-Iron. (2010). A behavioral-systems perspective on prosocial behavior. In M. Mikulincer & P. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angles of our nature (pp. 73 - 91). American Psychological Association.

Shaver, P., Segev, M., & Mikulinicer, M. (20111). A behavioral systems perspective on power and aggression, In P.R. Shaver & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), Human aggression and violence: Causes, manifestations, and consequences (pp. 71 - 87). American Psychological Association.

Shaver, P.R. , Mikulincer, M., & Shemesh-Iron. (2010). Ibid, 8.

Shaver, P., Segev, M., & Mikulinicer, M. (20111), Ibid, 9.

Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Campbell, C., Luyten, P., and Debbané, M. (2023). Cambridge guide to Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT). Cambridge University Press.

Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Campbell, C., Luyten, P., and Debbané, M. (2023). Ibid, 12.

Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Campbell, C., Luyten, P., and Debbané, M. (2023). Ibid, 12.

Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Campbell, C., Luyten, P., and Debbané, M. (2023). Ibid, 12., p. 34.

Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Campbell, C., Luyten, P., and Debbané, M. (2023). Ibid, 12.