As I described briefly in the last chapter, the Reflective Function (RF) Enneagram is a model that I have developed over the last thirty years, first as a student of the Narrative Tradition (beginning in 1995); then in the course of earning my PhD in Human Development (completed in 2010); and most recently with my independent research on mentalization theory and the work of Evagrius (ongoing).

Specifically, the RF model represents an integration of Helen Palmer’s teachings in the Narrative Tradition with several other sources including:

My doctoral research on the relationship between adult attachment styles and Enneagram types

Shaver and colleagues’ research on the relationship between behavioral systems and adult attachment styles

Fonagy and colleagues’ research on mentalization processes

Research on Evagrius’s model of spiritual development and his use of narrative methods to identify and work with obstacles to contemplation

In this chapter, I want to try to explain to you what the reflective function is and why I see it as the heart of the RF model of the Enneagram.

Mentalization Theory and the Reflective Function

In order to talk about reflective functioning I need to talk about mentalizing, and in order to talk about mentalizing I need to talk about reflective functioning, so please bear with me for a few moments here.

Reflective Function is a construct used in mentalization theory

Mentalization theory refers to the broad, deep body of work that has grown out of, updated, and even transformed attachment theory.1

Mentalization is at once a simple, familiar concept - all of us are engaging in some form of it almost all the time - yet at the same time an extraordinarily complex topic that requires some work to understand. In 2008, Fonagy and Bateman wrote:

“We propose boldly that mentalizing - attending to mental states in oneself and others - is the most fundamental common factor among all psychotherapeutic treatments and, accordingly, that all mental health professionals will benefit from a thorough understanding of mentalizing and from familiarity with some of its practical applications.”2

The authors go on to provide a concise description of mentalizing:

“The gist of mentalizing is holding mind in mind… We are mentalizing when we are aware of mental states in ourselves or others - when we are thinking about feelings, for example… More elaborately, we define mentalizing as imaginatively perceiving or interpreting behavior as conjoined with intentional mental states.”3

Mentalization and Reflective Functioning are synonymous

The terms mentalization and reflective functioning are basically synonymous, though historically “reflective function” has been used more with reference to mentalization processes that occur in the context of attachment relationships.4

Sharpe and Bevington (2022) define reflective function as, “the quintessential human capacity to understand ourselves and others in terms of intentional mental states, such as feelings, desires, wishes, goals, and attitudes…”.5

As described by Fonagy et al. (1998),

“RF involves both a self-reflective and an interpersonal component that ideally provides the individual with a well-developed capacity to distinguish inner from outer reality, pretend from ‘real’ modes of functioning, [and] intra-personal mental and emotional processes from interpersonal communications.”6

Assessment of Reflective Functioning

The reflective function construct has its origins as a subscale of the Adult Attachment Interview.7

RF is assessed on a continuum of functioning. At one end of the continuum is “Negative RF” which includes, “active, hostile resistance to the mentalizing stance; derogation of reflection; bizarre or frankly paranoid attributions - all in the context of a total absence of any reflection.”8

At the other end of the continuum is “Exceptional RF”, which includes, “rare cases of exceptional sophistication, coupled with consistent maintenance of a reflective stance throughout; integrating several instances of reflectiveness into unified and fresh perspectives; full and spontaneous reflection with respect to a range of relationships across the speaker’s life history.”9

The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire

In addition to the AAI sub-scale, a variety of other instruments have been developed to assess RF. The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire10, for example, is an eight item instrument that asks people to rate their agreement with eight statements on a scale from 1 to 7, with 1 indicating no agreement and 7 indicating full agreement. I am including the complete RFQ here so you can get a general sense of the kinds of questions used to assess RF:

1. People’s thoughts are a mystery to me

2. I don’t always know why I do what I do

3. When I get angry I say things without really knowing why I am saying them.

4. When I get angry I say things that I later regret

5. If I feel insecure I can behave in ways that put others’ backs up

6. Sometimes I do things without really knowing why

7. I always know what I feel

8. Strong feelings often cloud my thinking

Reflective Functioning and Social Cognition

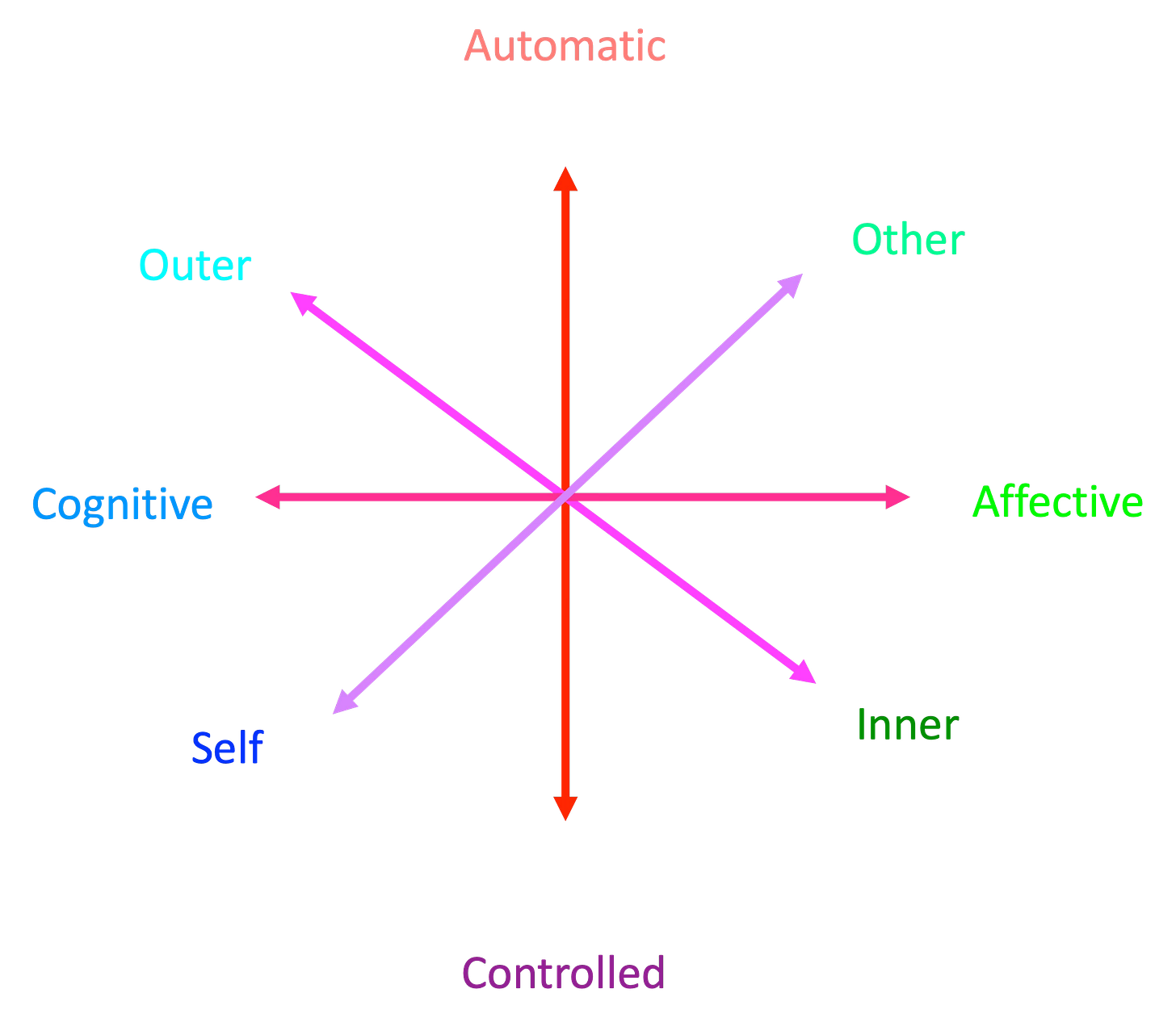

While RF is a unidimensional construct, it actually assesses a person’s capacity to appropriately make use of four dimensions of social cognition. As Duschinsky and Foster (2021) explain, there are: “… four ‘polarities’ of mentalization: internal and external; affective and cognitive; self and other; implicit and explicit.”11

Four dimensions of awareness that support reflective functioning

Duschinsky and Foster (2021) also note that Fonagy and colleagues, “proposed these polarities as, “the most significant areas of potential individual differences in mentalizing” (emphasis added).12

Individual Differences in Reflective Functioning and “Flavors” of Personality Disorders

Confirming Fonagy’s intuition that imbalances in the dimensions of awareness were related to individual differences in mentalizing, researchers have identified patterns of imbalance associated with various personality disorders. As Bateman and Fonagy (2019) explain,

“To mentalize effectively requires the individual not only to be able to maintain a balance across [the four dimensions] of social cognition, but also to apply them appropriately according to context…. In an adult with personality disorder, for example, consistently imbalanced mentalizing on at least one of the four dimensions would be evident. From this perspective, different types of psychopathology can be distinguished on the basis of different combinations of impairments along the four dimensions (which we refer to different mentalizing profiles).13

This research is central to Mentalization Based Therapy (MBT), which takes the view that all personality disorders arise from the same source - difficulties in mentalizing - but also recognizes and addresses the different patterns, or “flavors” of ineffective mentalizing as they present in the clinical setting.14

Linking “Flavors” of Personality Disorder with “Flavors” of Enneagram Types

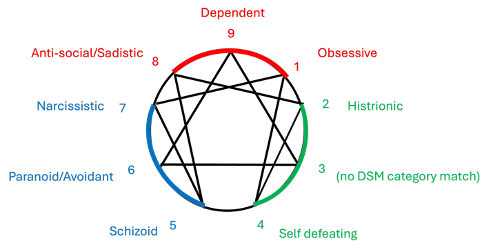

The research findings supporting the view that personality disorders are best understood as different patterns of ineffective mentalizing arising from a common source (ineffective mentalizing) calls to mind Naranjo’s observation that the extreme expression of the Enneagram types resemble personality disorders.

As I wrote in my chapter on Naranjo:

Naranjo recognized that for each Enneagram type there is a continuum of distress caused by the activity of the personality. At the low end the activity is almost imperceptible; at the high end the activity of the personality results in personality disorders. Most people are usually functioning at some point along this continuum.

Naranjo observed that, “While in the case of the ennead-types we find that it coincides with a known clinical syndrome, it is also true that everybody may be regarded as the bearer of one personality orientation or another, and that each may be seen in specific levels ranging from that of psychotic complication to that of the subtlest residues of childhood conditioning in the life of the saints.”15

Naranjo’s Enneagram of Personality Disorders

Naranjo depicted the generic Enneagram type as functioning on a continuum, from a “saint like” almost imperceptible personality pattern at one end to an extreme, rigid pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors at the other end, defined as personality disorder.

Some thirty years after Naranjo made this observation, research on reflective functioning appears to be making a similar discovery.

Effective Mentalizing and Palmer’s Reflective Stance

As described in the MBT literature, when a person is able to smoothly and appropriately move back and forth among the four dimensions of social awareness, reflective functioning is unimpeded and effective. A person in this state is able to engage with themselves and others from a stance of not-knowing and inquisitiveness.16

To me, this stance is the same as the stance described and taught by Helen Palmer, which she called the state of receptivity. Palmer wrote:

“The passion is emotional. It acts in concert with thoughts and phsyical sensation. To get beyond personality, thoughts and feelings are quieted and awareness shifted to a higher mental and emotional center. When successfully activated, the inner, or “higher” centers convey impressions from what is called objective reality, or essence. Objective perceptions are not distorted by the bias of type. They are not projections. They are views of the real. The activated inner centers are receptive to grace, or impressions conveyed from the realms of essence.”17

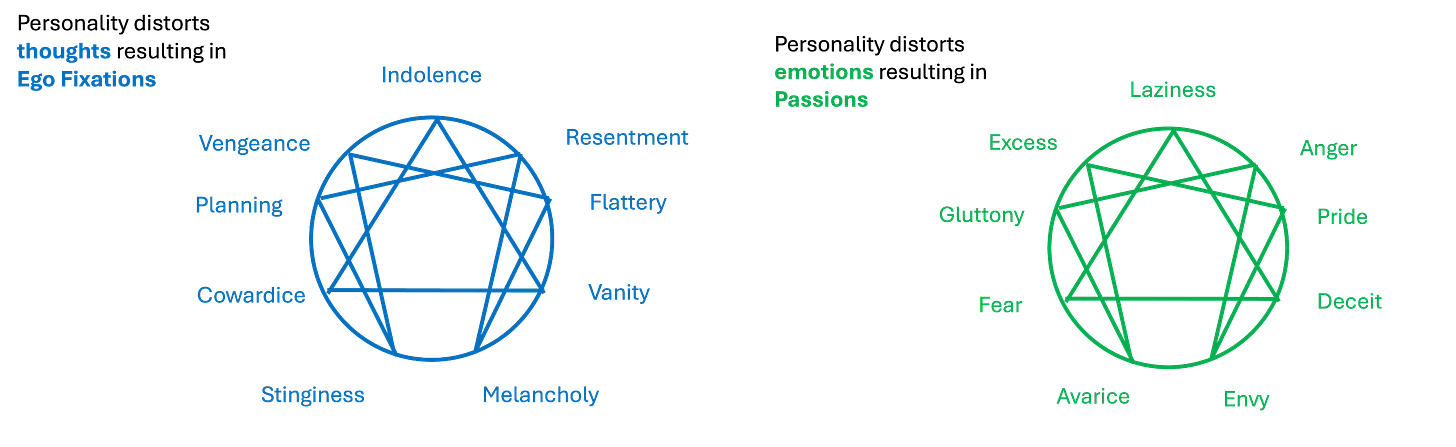

Ineffective Mentalizing and Ichazo’s Cognitive-Affective Distortions

Most of the time, most of us are not in a state of full mentalizing or receptivity. Helen was explicit in her teaching that we don’t want to be in state of receptivity when we are “driving in traffic”. Helen repeatedly emphasized that we need our personalities to engage in many, if not most, of our daily activities. Similarly, full mentalizing is probably not appropriate in many day to day situations. For example, if someone casually asks, “How’s your day going?” as a social convention, the appropriate response is usually similarly cordial but brief – “fine, thanks” or “could be better”. An interaction like this does not require full mentalizing, and such a stance could even be experienced as intrusive.

Though often full receptivity is not a necessary or even appropriate state, we do need a rudder, as Helen called it – something that is always running in the background that keeps us informed about our own state and the state of others. Most importantly we need something that can alert us to to a need to pause and consciously shift out of a “walking around” stance into a state of receptivity, or full mentalizing.

The RF model proposes that the cognitive-affective distortions that Ichazo first described and mapped onto the Enneagram symbol and that were later refined first by Naranjo and then by Palmer can be understood as rudders that serve to inform us of the need for a pause and a turn to explicit mentalizing. Put another way, the RF model proposes that Ichazo’s cognitive-affective distortions can be described as nine different expressions of ineffective mentalizing.

Ichazo’s Affective-Cognitive Distortions

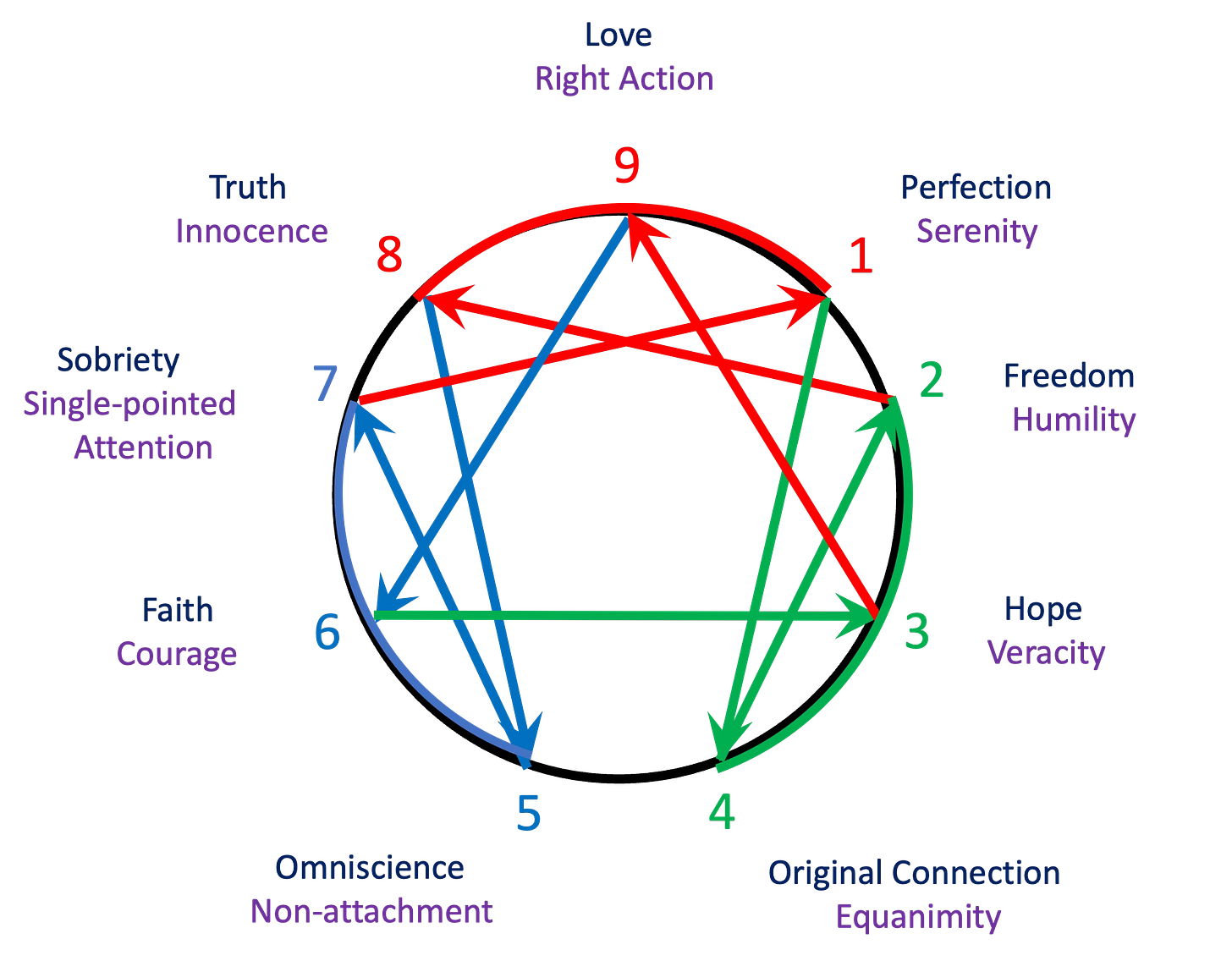

Effective Mentalizing and Ichazo’s Affective-Cognitive Virtues

And finally, by extension, we can read Ichazo’s map of affective-cognitive virtues as a map of nine different flavors of full, effective mentalizing.

Fonagy, P, Gergely, G., Jurist, E. and Target, M. (2002). Affect Regulation, Mentalization, and the Development of the Self. Other Press.

Allan, J.G., Fonagy, P., and Bateman, A.W. (2008). Mentalizing in Clinical Practice (p xi). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Ibid 2.

Duschinsky, R. and Foster, S. (2021). Mentalising and Epistemic Trust: The Work of Peter Fonagy and colleagues at the Anna Freud Centre. Oxford University Press.

Sharpe, C. and Bevington, D. (2022). Mentalizing in Psychotherapy: A Guide for Practitioners. NY:The Guilford Press (p 190). The Guilford Press.

Fonagy, P., Target, M., Steele, H., and Steele, M. (1998). Reflective-Functioning Manual Version 5 for Application to Adult Attachment Interviews. UCL Discovery.

Ibid 4.

Ibid 6, p 28.

Ibid 6, pp 30 - 31.

Fonagy P., Luyten P., Moulton-Perkins A., Lee Y.W., Warren F., Howard S., et al. (2016). “Development and validation of a self-report measure of mentalizing: The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire”. PLOS ONE.

Ibid 4, p 82.

Ibid 4, p 82.

Fonagy, P. and Bateman, A.W. (2019). Introduction. In Bateman, A.W. andFonagy, P. (Eds.) Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice, 2nd Edition (pp 3 - 20). American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Ibid 5.

Naranjo, C. (1994). Character and neurosis: An integrative view. Gateways/IDHHB, Inc. p, 44.

Ibid 2.

Palmer, H. (1993). The Enneagram in Love & Work: Understanding Your Intimate & Business Relationships (p 25.) HarperCollins.