Towards Resolving the Mystery of the Heart Center

Reimagining the functions of the Heart center in terms of Caregiving

In the last chapter we looked at the lack of agreement in the Enneagram literature about the qualities that comprise the Heart center. While the literature shows a good amount of agreement about the qualities of the Head center (characterized by issues associated with the emotion of fear) and the qualities of the Belly center (characterized by issues associated with the emotion of anger), there seems to be very little agreement about the qualities of the Heart center, including what emotion best characterizes these qualities.

However, despite the lack of agreement about the chief characteristics of the Heart center, all these models share an emphasis on understanding the Heart types as being organized around moving towards another in service of one’s own needs.

Ichazo, Naranjo and Palmer all describe the Heart center in terms of moving towards others in support of needs for approval, being seen as valuable, or being seen as special. The PDP model provides an explanation for this moving towards behavior with their “vector” component, which describes the Heart types as being motivated to move towards others in support of the attachment-based need for bonding.

The models vary in their descriptions of what specific needs are being addressed, but they mostly agree that the Heart types are organized around moving towards others in service of one’s own needs. However, I notice something is missing in these models.

The vibes that I associate with the Heart center have a lot to do with feelings like happiness, optimism, and playfulness (including the sadness associated with type Four, which involves the absence or loss of these hedonic experiences).1 Put simply, I don’t see this vibe being accounted for adequately in any of the existing descriptions of the Heart center.

Reimagining the functions of the Heart

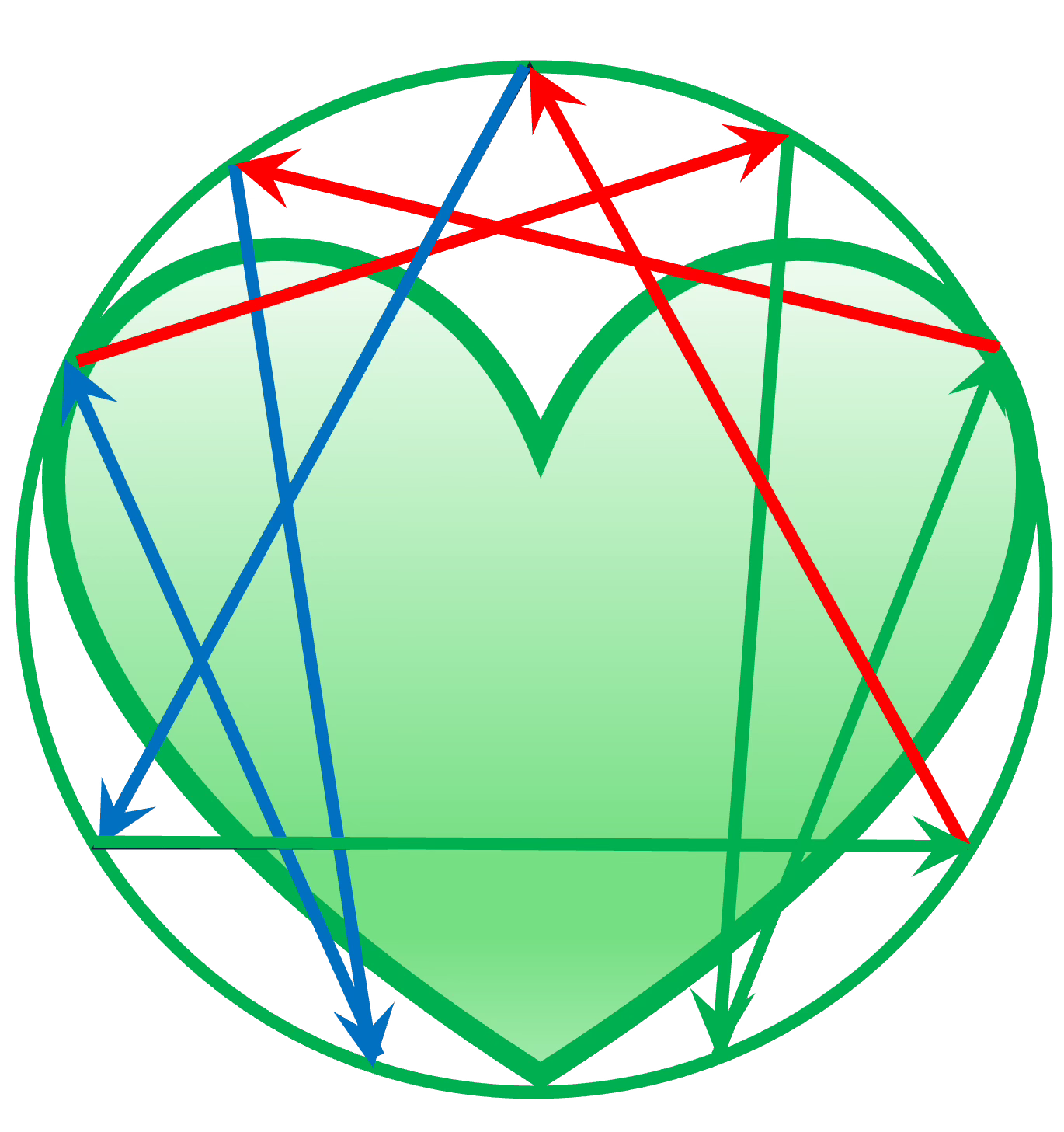

In my own model of the Enneagram, the “moving towards” behavior associated with the Heart center is described as arising from the caregiving behavioral system as described by Mikulincer and Shaver (2010)2. In contrast to the attachment system, which supports moving towards another in support of one’s own needs, the caregiving system supports moving towards others in service of the other’s needs:

As Mikulincer and Shaver (2010) explain, “Bowlby… described the goal of the caregiving system as reducing other people’s suffering, protecting them from harm, and fostering their growth and development… That is, the system is designed to serve two major functions: to meet another person’s needs for protection and support in times of danger or distress (Bowlby called this ‘providing a safe haven’), and to support others’ explorations, autonomy, and growth when exploration is safe and desirable (Bowlby called this ‘providing a secure base for exploration’). From this perspective, the goal of the care seeker’s attachment system – to maintain a safe haven and a secure base – is also the aim of the care provider’s caregiving system. When a caregiver’s behavioral system is activated by a person who needs help, the system’s primary strategy is to perceive the needy individual’s problem accurately and provide effective help. When this help is successful, the caregiver’s caregiving system is satisfied and, for the moment, deactivated.”3

Research on helping behavior in rats

Researchers who study helping behavior in rats have concluded that the caregiving system initially evolved because mammals are ‘altricial’ (born quite helpless) and mammal mothers needed to be motivated and able to provide effective care to their babies. However, this system, which is thought to have originated as maternal behavior, has generalized in both humans and at least some other mammals, well beyond the mother- infant relationship such that the caregiving system serves to motivate helping behavior in general, not just in infant care situations.4

Research has shown that rats are motivated to move towards other rats who are in distress, even though this action is dangerous and frightening for the helping rat. 5

Peggy Mason, a leading researcher on rat empathy and helping behavior, describes the helping behavior of the rat as involving a two step emotional process. The helper rat has to first down-regulate his own fear before he can engage in helping behavior that involves an optimistic, exploratory state of energy and attention. Mason uses a paradigm in which one rat is restrained in a clear tube and another rat is free to move around the arena. Mason explains, “Active helping requires that the helping rat down-regulate the fear he is experiencing through emotional contagion… the helper has to suppress his natural response of frozen immobility and actually move to help the other rat…Even though it takes quite a bit of rat courage to venture into the scary arena center, the free rat persists in moving to the center and trying to figure this restrainer thing out so he can help his cage mate.”6

Mason says that when the helper rat is able to successfully free the restrained rat, “it looks like a celebration” as the two rats race around the arena together in what appears to be a state of joy. 7

Mason’s team has shown that the hedonic experience of helping a needy rat is so powerful that rats choose to help a restrained rat even when there are chocolate chips available, that the helper rat could eat alone. Instead, the helper rat first frees the restrained rat and then the two rats share the chocolate chips, indicating that the caregiving system involves hedonic states, even more pleasurable than eating chocolate chips alone. 8

The Caregiving system in humans

We see evidence for the Caregiving system being associated with hedonic states in human development as well. Even very young, pre-verbal infants exhibit a preference for helping behavior in others, and toddlers are eager and able to happily provide help to others in need.

Mikulincer and Shaver (2010)9 describe how differences in adult caregiving styles appear to be related in theoretically predictable ways with differences in adult attachment styles.

As Colledani et al. (2022) explain: “According to attachment theory, the propensity of human beings to care for others is governed by an inborn caregiving behavioral system that aims to promote welfare and reduce the distress of other people through effective provision of care. However, some individuals may develop non-optimal caregiving strategies, such as anxious hyperactivation and avoidant deactivation.” 10

Hyperactivated caregiving: “… is characterized by effortful care provision that is intrusive, anxious, and poorly timed. It can be motivated by a desire to feel competent and admirable as a caregiver of by a need to make oneself indispensable to a partner. To achieve these goals, people prone to hyperactivated caregiving tend to exaggerate others’ needs and intrusively prose them to accept help.” 11

Deactivated caregiving: “… involves inhibition of empathic concern and caring for needy others, lack of sensitivity and responsiveness to others’ needs, and a tendency to cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally withdraw from people who are seeking care and comfort.” 12

The Caregiving system and Enneagram types

In my doctoral research, I found some support for the idea that the Enneagram types can be understood as nine different versions of insecure attachment style, and by extension, nine different pathways to security.

My model of the Enneagram centers associates the Head center with the attachment system and the Heart center with the caregiving system. Because activation of the caregiving system appears to involve deactivation of the attachment system, we can think of the Heart center in terms of the core type (Three) representing a general suppression of the attachment system in the service of a general activation of the caregiving system.

Type Two would be seen as representing a more extreme suppression of the attachment system in association with a greater activation of the caregiving system than Type Three.

Type Four would be seen as having an insufficient suppression of the attachment system, with an associated muting of the caregiving system, resulting in an absence of the hedonic experiences associated with the caregiving system.

Future research could explore these predictions both through the use of the CSS and through qualitative interviews13.

Summary

The Heart center has traditionally been understood to involve a function of moving towards others in service of one’s own needs (various models identify needs such as approval, bonding, recognition, etc.) However, these descriptions do not seem to account for the optimistic, hedonic, other-oriented attention and energy states that are associated with the Heart center (this includes the sadness and longing states that are part of the type Four structure, since these states involve attention to the absence of joyful, hedonic experiences).

In this chapter I have argued that reimagining the Heart center in terms of the mammalian caregiving system better accounts for the qualities of the Heart center types, and I made predictions about how the caregiving styles might show up in the three Heart types.

Conclusion

This chapter concludes my review of the Enneagram centers literature. For the next phase of work, I am turning my attention towards developing and teaching a new Enneagram typology, which I am calling the Reflective Function model.

I am grateful for your companionship on this journey so far, and I look forward to you joining me on the next phase of the adventure.

I am indebted to Monirah Womak for teaching me about the “fun” qualities of the Heart center.

Shaver, P.R., Mikulincer, M. & Shemesh-Iron, M. (2010). A behavioral perspective on prosocial behavior. In M. Mikulincer & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 73 – 91). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Shaver, P.R., Mikulincer, M. & Shemesh-Iron, M. (2010), ibid, 1. pp. 42 - 43.

Ben-Ami Bartal, I., Decety, J., & Mason, P. (2011). Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science, 334(6061), 1427 – 1430.

Peggy Mason, ibid, 3.

Ben-Ami Bartal, I., Decety, J., & Mason, P. , ibid, 4.

Shaver, P.R., Mikulincer, M. & Shemesh-Iron, M. (2010), ibid, 1.

Celledani, D., Meneghini, A.M., Mikulincer, M. & Shaver, P.R. (2022). The Caregiving System Scale: Factor structure, gender invariance, and the contribution of attachment orientations. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 385(5), 385 – 396.

Celledani, D., Meneghini, A.M., Mikulincer, M. & Shaver, P.R., ibid, 9, p 385.

Celledani, D., Meneghini, A.M., Mikulincer, M. & Shaver, P.R., ibid, 9, p 385.

Palmer, H. (1988). The Enneagram: Understanding yourself and others in your life. San Francisco, CA: Harper Collins.

Hi Kristin, I'm reading Daniel Siegel (and the PDP group's) book "Personality and Wholeness in Therapy," where they draw upon Jaak Panksepp's work. He identifies four distinct appetitive emotion systems, including: SEEKING (anticipation-reward system with regard to all manner of needs and desires); CARE (fuels the drive to help others); PLAY/SOCIAL/JOY (drive to have fun and be creative and spontaneous, to exert agency wisely, manage interpersonal connections, and discern the difference btw opportunity and threat); LUST (involving the motivational energy of sexual attraction and desire for sexual activity). They say "Panksepp's four appetitive motivational networks are likely all involved to various and nonspecific degrees in each of the three aversive motivational networks' activations." Further, they state: "Jaak Panksepp's descriptions of the three aversive affective states (anger, sadness/separation distress, and fear) seem to help in distinguishing the three clusters of personality patterns, while the four core subcortically mediated appetitive ones do not divide into these groupings seen in the narrative data we have." They ask "Might there be another system that could use these appetitive emotions to organize another aspect of personality?" Jack Killen may be exploring the system of subtypes. "In our informal observations as a PDP group, we do see these four appetitive systems equally distributed across the nine PDPs, but are fascinated to see how each subtype within each of these pathways might be shown to correlate with these other appetitive networks' activity....." I love your work, thanks for posting! -Kerry O'Donnell